|

Soundtrax: Episode 2009-10

August 31th, 2009By Randall D. Larson

Charles Bernstein Music for the Macabre: The Sci-Fi, Horror, & Thriller Scores of Charles Bernstein

A Career-Spanning Interview with the Composer

Q: You have said that music has a powerful ability to communicate terror in a horror film. In your own film scores, in general, what do you feel has been your technique to achieve this and to enhance the terror inherent with the genre?

Charles Bernstein: I try to approach each score as an actor might, by delving into the very particular character of the film. Each film seems to dictate its needs musically. I like to let the film tell me what it requires, rather than the other way around. The trick is to be open to what it is that the film and the director are really looking for.

Q: One of your first scores, in 1972, was for a horror thriller called Daddy’s Deadly Darling (aka Daddy’s Girl, Pigs, The Strange Exorcism Of Lynn Hart, etc). As your first foray into feature horror film scoring, do you recall your approach to scoring the film or how you determined what type of music would best support this kind of picture?

Charles Bernstein: This film was written and directed by the interesting character actor, Mark Lawrence. He was well known for his roles playing bad guys in hundreds of films and TV shows. He had no money to pay me, so I agreed to do the score in return for a painting by his artist son, Michael Lawrence that had originally been painted for Federico Fellini. I wrote a creepy nursery rhyme for female voice to accompany the demented character played by Mark’s daughter, Toni. I also wrote an odd song for the opening entitled “Somebody’s Waiting for You.” I had to record it at home and sing it myself (due to no budget). I am not a singer by any stretch of the imagination, but I think the weird performance and primitive production values actually helped create a foreboding mood. This was a very early foray into the use of home studio scores that have become so popular in recent years.

Q: The unusual psychological thriller, Sweet Kill (1973) was about a maniac who “loves” women to death. How would you describe your approach to scoring this picture?

Charles Bernstein: I worked closely on Sweet Kill with the terrific director Curtis Hanson (L.A. Confidential, 8 Mile, etc.). At the time, I had been heavily influenced by the moods in certain European film scores, particularly Claude Chabrol’s work with composer Pierre Jansen on films like La Femme Infidèle (1969). I began to incorporate unusual sounds to heighten the suspense. In this score I remember bringing some sleigh bells to the set when Curtis was filming a murder scene with actor Tab Hunter. I announced to them that I was planning to score one of the killings with a reverberated recording of these bells that should feel like the insane clatter in the mind of the homicidal character. Needless to say, they probably wondered about my own sanity. I also used bass flutes, Indian tabla (played by Emil Richards), and low register piano to create a palette of sounds to highlight the dark lyricism of Tab’s sort of love/hate character.

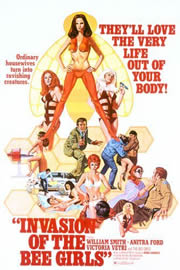

Q: Your music for the exploitation classic Invasion Of The Bee Girls (1973) seemed to take some of its sound from the suggestive buzzing of bees. How did you enhance its various nuances with your score?

Charles Bernstein: I had already written the music for an Oscar winning documentary directed by Denis Sanders (Czechoslovakia 1968) when he called me to score this strange little film (which was written by the talented filmmaker Nicholas Meyer). I used electronic bee-buzzing sounds as well as twangy percussion effects and otherworldly voices to create a campy flavor, including a mock-serious “Amen” choral piece for women’s voices and synthesizer bee-buzzing for the big transformation scene. The overriding purpose of the music in a film like this is to let the audience know that the movie is intended to amuse, not to frighten.

Q: You scored a number of contemporary action thrillers in the early-mid 70s, such as White Lightning, Mister Majestyk, Gator, Viva Knievel! and the like. In general what type of music was demanded of films like this and what did you do to bring your own voice to action scores like this?

Charles Bernstein: In these rural action pictures, I tried to come up with a musical language that had an edgy, percussive, regional flavor. I often mixed synthesizers and wah-wah electric guitars with acoustic folk instruments such as banjo, dobro, jaw-harp, harmonica, and fiddle as well as full orchestra. Director Quentin Tarantino has borrowed some of my cues from White Lightning to use in his recent films.

Q: When you scored Look What’s Happened To Rosemary’s Baby (1976), was there any requirement or need to tie in your score with that of the film’s predecessor?

Charles Bernstein: I took a very different approach to this sequel. I chose a more Catholic gothic direction utilizing chorus, orchestra, chimes, and frequent references to the “Dies Ire” chant from mass. I felt that the wonderful lullaby worked well for the baby in the original, but that the darker, somber colors played better for the script of the sequel.

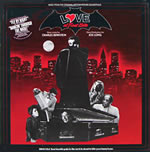

Q: Your score for Love At First Bite (1979) included a neat solo violin melody akin to that of the old Universal classics, and your music generally played straight man to the film’s comedy. How did you work out your music for this film?

Charles Bernstein: Yes, the music was intended to be an orchestral super-serious Folk Rumanian background for George Hamilton’s hysterically funny vampire. I chose the solo violin as the voice for his centuries-old sentimental longing. The music was very much the straight man in this approach.

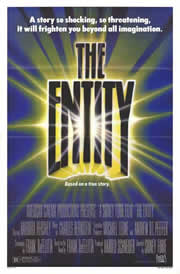

Q: The Entity (1981) was another powerful horror score, featuring a ferocious electric guitar motif to delineate the plunderings of a suburban poltergeist. How did you work out this score?

Charles Bernstein: On this one I worked very closely with director Sidney Furie. I home-recorded various musical cues that we knew we would be needing and we divided them into categories that Sid nicknamed for convenience, such as “The Thrasher,” “High Dread,” “Low Dread,” etc. Then we refined them to best effect. In 1982, this was a very early use of a composer/director method that is now quite common: to audition and shape the music before doing a big recording session.

Q: Cujo (1983) featured an especially menacing and atmospheric score that intensified the film’s mood of sudden, claustrophobic terror in the midst of the bright outdoors, punctuated by a recurring (and progressively more savage) piano and synth ostinato for the rabid Saint Bernard. How did you develop your progressive musical style for this film and what led to your choice of instrumentation?

Charles Bernstein: I worked closely with director Lewis Teague and producer Dan Blatt while writing that score. I remember being well into the score, much of which involved an orchestral approach to a family in crisis, before coming up with the darker elements, including Cujo’s theme (low French horns). As Lewis pointed out, it was the emotional family material at the beginning that makes the menace feel so powerful later on.

Q: Your music to Nightmare On Elm Street (1984) captured a great sense of foreboding its frantic rock beat balanced by low synth pulses under higher, floating electronic tones and twinkles. Was the predominant use of synth an aesthetic or budgetary choice on this film, and how did you utilize this instrument in a new way to enhance the film’s dreamy horror and fantasy?

Charles Bernstein: The director, Wes Craven, was very knowledgeable and engaged in the scoring. The dominant use of electronics, however, was dictated by the very small package-deal budget. Had there been more money, I would have mixed the electronics with orchestral elements. But the synth colors were always necessary for the vision of the score. This was a home studio recorded score, which in 1983 was very uncommon, if not unheard of, for a feature film.

Q: One of the things music needs to do in a film like Nightmare On Elm Street is to help create the fantasy’s organic environment; in this case, Freddy Krueger’s incursion into the dreams of the protagonists. Were you conscious of doing this when scoring the film, and what elements of the story did you feel needed to be central to your musical approach?

Charles Bernstein: Well onto the writing process, I asked director Wes Craven if he would be open to my using a real theme, a melody that I would develop and adapt to the unfolding story. He was very open to the idea and this allowed me to go in a musical direction that felt right to me. The use of a recurring theme helped me to suggest Freddy’s presence musically when he was not on screen.

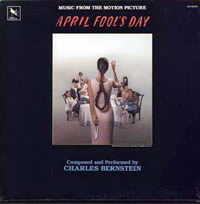

Q: With April Fool’s Day (1986) you definitely joined the ranks of slasher movie composers. The score mixed synths with a notable children’s chorus, which nicely contrasted the idea of innocence with that of the unseen holiday killer. Do you recall how this score and its thematic/motific interplay was developed?

Charles Bernstein: This film was temp tracked by master music editor John Strauss with music from Bartok’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste and other 20th Century masterpieces. It was great, but I had to totally rethink the musical approach to make sure that the send-up of the genre and the youth culture elements connected. Hence, the use of a whistling motif and children’s voices were added to the harder hitting elements and the orchestral settings. I also wrote a tongue-in-cheek ending song, “Too Bad You’re Crazy,” to send the audience away in the proper smiling frame of mind.

Q: What elements became central to your score for Wes Craven’s Deadly Friend?

Charles Bernstein: This score clearly called for a “robotic” electronic component for the robot Bebe, as well as a traditional orchestral score to carry the normal moments. Both of these approaches needed to reflect the commonplace as well as the horror aspects of the film. I did the electronics myself and we recorded the orchestra afterwards, integrating the two as needed.

Q: 1995’s Rumpelstiltskin put a new spin on the fairy-tale inspired horror film. What was unique about this assignment for you?

Charles Bernstein: This was really challenging. Part of the film was mythic medieval/gothic and part was very contemporary/cops. The trick was to create a musical environment that didn’t sound too divided, but met both of these time frame’s needs. The use of thematic material helped in this regard, as did the melding of pop and traditional techniques.

Q: What type of score for The Day The World Ended need?

Charles Bernstein: I took my cues from the talented avant-garde English director Terry Gross and the producer, Lew Arkoff, both of whom had very strong and specific ideas for the score. I certainly would have used a real orchestra had the budget allowed. I ended up using a simulated orchestral approach and tried to go with the scary and the creepy as much as possible.

Q: You’ve composed many different types of films over the last 40+ years, but your efforts for horror films have always stood out. What is it about music for this genre that encourages its composers to write so much expressive and intense music?

Charles Bernstein: Fortunately, horror films rely a great deal on music for their effectiveness. This gives composers like me a chance to do our part in moving the audience. These films also often invite originality, stylistic exploration and innovation. Who can resist that?

Q: What do you find distinctive about your horror scores and how have you tried to give this prolific genre your own musical voice? What has been most challenging about scoring films in this genre?

Charles Bernstein: I never listen to other horror scores when I approach an assignment. My method is more like that of a method actor, to reach down into my own emotions and work from there. I hope that this produces and authentic and personal score, but I am just happy if the film is made better from my efforts.

Q: Relatively few of your scores are available on soundtrack recordings, LPs or CDs. Gator was recently reissued on iTunes and Mr. Majestyk on CD by Intrada. Any prospect of seeing more of your scores issued this way or on specialty CD?

Charles Bernstein: Yes, fortunately there has been more interest in my existing scores lately. I am also happy that so many wonderful scores of my fellow composers are being released to the public. There seems to be an upsurge in interest in the art and craft of film scoring. For this we can all be grateful! Thank you for playing such a large part in promoting this interest and in educating so many listeners and film goers about our mysterious and rewarding profession.

New Soundtrax in Review

Drag Me To Hell reunites Christopher Young with director Sam Raimi, and Raimi with the terror tales that were his introduction into filmmaking. Young (who previously worked with Raimi – director on The Gift and Spider-Man 3; producer on The Grudge and The Grudge 2), supports the film with a score that is both shocking and poignant, rendering the story in colors of hellish gray and brown, dissonant rushes of sound design and chaotic chorale, but not at the expense of the warmth of graceful melodies and delicate phrasing from strings and winds. Released on CD by Lakeshore, Drag Me To Hell is an ideal horror score in that it soothes as it scares, it provides respite and reassurance even in the midst of relentless, raging disharmony. The main melodic theme, piano over sampled voice and hushed synths, is one of Young’s loveliest melodies, heartbreaking in its simplicity and presentation here (“Tales of a Haunted Banker,” “Familiar Familiars,” “Brick Dogs Ala Carte”) and his opening cue is a splendid overture of melody and madness, a persuasive violin melody over horns and choir, making room for dramatic intonations of brass and winds, growing strains of keyboards and pulsing horns, upturned choral yells, but with a classic melody than runs through it all, rich in power and a kind of harsh eloquence. Throughout the score, there are suggestions of the kind of sound-mass scoring that Young defined years ago in Hellraiser, although the score is characterized by a more delicate means of evoking the scary/spooky, compelling melodic fragments share space with heavy configurations of massive sonority; tender filigrees of strings and wind and voice shoulder their way in amongst bestial throngs of blaring textural construct; a sweet, caring soprano caresses while snarling blocks of oozing sound confront (“Ordeal by Corpse”). There are some surprises. “Ode to Ganush” emits a curious jazzy, bass riffing amidst furtive synth and fiddle tonalities and, eventually, an explosive synth reveal. The carnival atmosphere swells back up in “Auto-Da-Fe.” “Loose Teeth” wriggles with wobbling tonality, bristling snare brushings, sustained strings, woo-ing progressions of choral the opens with a warm-up conflagration of orchestral instrumentation, batwinged strings and snakerattling percussion, and that jazzy bass and pounding drum riff giving it all a sense of movement and direction and downward spiraling purpose, a gruff voice welcoming all to the cheery abode of eternal punishment. Oh, but there will be blood. There are moments of pure horror in the music. “Lamia,” for example, opens with a dissonant and disturbing shriek of sound that is very unnerving, wafting into a progression of wicked processed violin chills, clusters of clenched keyboard notation, whispering synth tones, and chaotic, demonic voicings. We have all been dragged a little bit into hell with this cue, but it opens into a diabolical carnival of tuneful cheer that could have been performed by the happy damned. Brooding, Herrmannesque measures close out the cue with ominous portent. It all comes together in the fragrant, sulfurous and mesmerizing “Concerto To Hell” that wraps up all of the score’s loose teeth and provides a thoroughly satisfying denouement.

Nicholas Hooper’s second and last visit to Hogwarts, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, sixth entry in the film series, with one more to go, has been released on CD by Decca. It is a delightful addition to the growing liturgy of Potter soundtrack music, following the essential mandate defined by John Williams in the first film and using brief bits of his Hedwig’s Theme and Quidditch March in the new score to tie it in, thematically, with what has gone before. This is Hooper’s second Potter score, having composed the last one, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Hooper has said he won’t be scoring the final film, the two part -and the Deathly Hallows (2010 and 2011), leading to conjecture (and fervent hope by many) that John Williams might return to close the circle on this cinematic franchise. Much of Half-Blood Prince has to do with Dumbledore, Hogwarts’ venerable and Harry-friendly headmaster, so Hooper has composed a moving choral piece for him, originally intended to be sung on screen by the Hogwarts school choir. That scene wound up being dropped, and the choral piece instead is heard over the end titles; but much of the score is drawn from the notation of that piece, so Hooper has moved it up into second position on the album in order to properly introduce the themes he will develop throughout the score. Musically this is a different animal than Williams’ original approach in the first and third entry, or that of William Ross evoking Williams in the second, and Patrick Doyle in the fourth; not only have the new composers integrated their own voices just as new directors have, but the series has matured over the years just as Harry has matured and grown up in wizarding school. The tone is not, and should not, be quite as innocent and carefree as that of the first film, and Hooper nicely evokes a more mature sensitivity without losing the basic sense of enchantment and fun that the series is drawn from. Potter’s essential morality play is well suited to the thematic approach taken by all of its composers, even if few of those themes aside from Williams’ primary motifs have been shared across the arc of the story. Hooper evokes the “Possession Theme” that he composed for Half-Blood Prince and which links arch villain Valdemort with his acolyte Tom Riddle; it forms a major motive for the second half of the score. Now that Harry is growing up, we have a couple of persuasive love themes, a very percussive sonority for the Death Eaters, and a brooding theme that reflects with sympathy the sorry choices made by Malfoy in his road from bullying into clear villainy. Lighter moments revolving around school life at Hogwarts. There are also a couple of cool swing tunes that figure in the story, the tantalizing “Wizard Wheezes” (which turned out not to be used in the film) and the concluding “Weasley Stomp” which are both a lot of fun. All in all a very fine score on its own, and a notable entry in the Potter pantheon of magical music. Hooper provides a valuable descriptive note about his thematic approach and how the unused choral motif was developed and what part of it remains integral to the score. Decca’s release appears on an enhanced CD that also allows download of the full score in 5.1 surround sound, an exclusive downloadable track (raucous modern rock, meh) and a behind-the-scenes featurette from the scoring session at Abbey Road Studios. Oh, and a ringtone, ho-hum.

Jean Prodromidès’ score for Albert Lamorisse’s Le Voyage En Ballon (1960; released in the US in a poor dubbed version as Stowaway In The Sky with heavy voice-over narration distorting the beauty of the music) is very much in the fashion of a Jules Verne adventure. The film, a follow-up to the director’s acclaimed short film, Le ballon rouge (1956; The Red Balloon) only with a much, much larger balloon, was essentially travelogue in which the boy from Red Balloon (Lamorisse’s son Pascal) stows away on a 60-foot balloon that his grandfather has made, and they have sightseeing adventures. The music, therefore, was an integral part of the French film, powering its sweeping landscapes with beautifully melodic and compelling music. The music is melodic and exuberant, evoking young Pascal’s wide-eyed marvel at cosmopolitan Paris, the splendors of the French Alps, the valleys of Alsace, hilly Provence, seaside Camargue, and more from 100+ feet up. Previously available on CD only in Japan (and that an abbreviated version of its French LP), Montreal’s Disques Cinémusique has released the score as an unabridged (12 tracks), remaster. The large orchestra and chorus score were vivid and colorful, and this remains one of the composer’s finest works for cinema. Thorough notes from ChristianTexier provide a valuable commentary on the music. The release also includes a 17:29 suite from the short film, Un Jardin public, a short feature from 1955 centered on the mime Marcel Marceau; the music hits all of the movements and expressions of Marceau’s mimeability and is a clever extended scherzo involving mostly strings and winds.

Mychael Danna has composed delicate and poignant score for The Time Traveler’s Wife, a science fiction drama about a man who inadvertently travels in time, which causes understandable frustration for his wife, left behind and all. Aside from two pop tunes and the brief segment of the German Christmas Carol, Es Ist Ein Ros that opens the album, we have 20 tracks of pristine Danna courtesy of New Line Records. Danna almost focuses primarily on underscoring the relationship between Michelle and Arliss, with a gentle sonority of piano and strings. The manifestation of time travel is accompanied by gamelan-styled gongs and bell-tree percussion (“I’m You Henry,” “Testing”), although the instrumentation is sometimes blurred between the two motifs. “I Never Had A Choice” gets into darker territory, with a synthetic undercurrent of rough tonality and slight percussive edge, but most of the score produces these beautifully passionate, yearning layers of warm melody and delicate, soft instrumentation, in a thoroughly engaging score.

Tyler Bates’s latest score finds him working with Rob Zombie again, on the director’s re-imagining of John Carpenter's Halloween II. The film picks up where Zombie’s Halloween left off, and focuses on the struggles of Laurie Strode (played by Scout Taylor-Compton) and killer Michael Myers (played by Tyler Mane). Bates’ score once again revisits the classic John Carpenter theme from the original film, but only for a moment, then dispenses with it and delves headlong into even darker and very distressing musical landscapes. This is horror music of the sound-design variety, bleak and vicious, as frightening to hear coming out of your home speakers as it surely will be in the film. It’s difficult music, tough to listen to. Unusual percussive electronic effects, heavy chords of synth and horn, and processed choral effects abound, creating a nightmarish tonality that is thoroughly unsettling. Track 14 is the least chaotic track, providing a sustained fluidity of ambient synths and voicings, but it too near the end revs up a motorized percussive riffing and a throbbing, industrial cadence that opens a bleak territory of brutal, sonic commotion. In crafting his sound design, Bates has put together an interesting array of textures, sound fragments, percussive tonalities (indeed), and grating sonic intensity. It may not warrant as much repeat playability as something with more melodic or tonal characteristics, but the score is completely captivating in its method of crafting scary music and upping the ante of fear in the film. The Halloween II score album comes courtesy of Bates’ new label imprint, Abattoir Recordings, digitally distributed by E1 Music. A physical CD release with previously unreleased music will follow with the DVD release of the film.

The Mutant Chronicles tells the story of the last mission of the only surviving humans on earth, a hopeless task which ends in bloody failure against an army of Mutants. The visual backdrop of muddy trenches and huge WW1 style weaponry is aided by the Richard Wells’ music. Released by Silva Screen Records. Reflecting the ever increasing futility of the mission, the score starts with a haunting melody in the trenches before the mission begins and then becomes ever more discordant as the survivors die one by one until the final violent act, accompanied by a dreadful dissonant cacophony. In the manner of Basil Poledouris’ Starship Troopers, this is a science fiction military score, mostly synths and samples but very effectively rendered, with a strikingly evocative main theme, plenty of action motifing, effective use of sampled choirs and epic tonalities in tracks like “The Killing Fields,” heroic eloquence (“Give Me Twenty Men”) and balls-to-the-wall action riffing in “Bonecrusher” and other muscular tracks. “Monastery” features some ethnic instrumentation and voicings; “Mitch and Adelaide” some poignant reflection. Quite likable.

After lurking around various compilations for many years, Toho film’s classic science fiction. Miniature effects-laden epics, The Mysterians (1957) and Battle in Outer Space (1959) have their complete scores finally available, courtesy of Toho Records as an exclusive 2-disc offering from www.arksquare.net Both scores feature the work of Japan’s monster maestro, Akira Ifukube, who develops themes and motifs the originally wrote for Godzilla into a potent musical mix for these pictures (Ifukube, like several other composers, interchanged his motifs between monster films and sci-fi, often in very different arrangements). What was Godzilla’s March becomes a proud, military march in The Mysterians, expanded into a powerful and spirited score for this lavish science fiction spectacle, and what was Godzilla’s angry monster music becomes a motif for the mysterious invaders, with ultra-low bassoon and tubas echoing severely beneath shimmering metallic twinges and tonalities. Ifukube provided a new Outer Space Theme for violin mixed with electronics, which in one place is effectively counterpointed against his signature requiem, the latter also initially written for Godzilla. It’s energetic and passionate in Ifukube’s great style. Battle In Outer Space is a very similar film and score, derived from much of the same material, but it worked as well here as it did in the previous film. Ifukube’s March figure is arranged over prominent snare drum beats, heard at one point very rapidly from chanting trumpets over frenzied drums and urgent brass bleats. The primary theme, however, is the Godzilla Horror motif, put through all manner of arrangements including solo French horn over piano, and low, raspy brass over rumbling percussion. A beautiful variant of the Requiem appears in Battle on track 8 for a hushed, poignant piano over whispering strings. Another recurring motif consisted of quick, low viola and piano notes in a thrice-repeated, four-note pattern. The basic tracks have been available but never in such detail, 20 tracks from each film, which allows for variation and nuances in the presentation to shine through. As with the previous expanded full soundtrack to Latitude Zero, these are richly composed and conveyed scores well deserving of expanded treatment.

Jeff Grace eschews the avant-garde stylisms of his previous scores(The Last Winter, The Roost, Joshua), most of which were designed for string quartet, and turns in a score designed for a somewhat larger orchestral ensemble with I Sell the Dead, released digitally and on CD by MovieScore Media. The film is a horror comedy starring Ron Perlman and Dominic Monaghan about the reflective memoirs of a graverobber. The score is uneven but ultimately likable, its fits the reflective nature of the character’s musings and occasional misgivings. The music is has a fine quirkiness to it, with an old fashioned and somewhat folk orientation to its melodic phrasing, and fits the maliciously self-indulgent and self-centered sensibility of the main character. Much of the music, in fact, sounds almost like a sordid and very macabre dance once the rhythm gets going. Eschewing major melodic variances, for the most part, Grace proceeds with a variety of figures and motifs he will bring out, like a graverobber unpacking his tools, when the story demands, which likable orchestration and a pleasing palette with which to work. The ultra low woodwind braaps of “Langols Island,” for example, set a curious tonality to the cue, while the workaday scherzo of “Wake Snatching” sets up a marvelous cadence for the caper. “A What Witch?” with its easy going, slightly off-kilter melody and rhythm, enhanced by ratchet and whistler, is a delight. “A Hard Slog” is an appealing track with a sirenlike violin motif swaying across wavering fields of windblown string strokes. “Dr. Vernon Quint at Your Service” is an evocatively mysterious string piece, characterizing the good Doctor in shades of malevolence and self-interest. “The Dead Undead!” opens into a bouncy romp for strings over winds, before changing direction again and shuffling off into meandering and clustered violins as a game of cat and mouse between dead and undead ensues. “A Cemetery Stroll,” is a very nice closer, opening with a dark, almost whimsical melody from solo trumpet over a lineup of strings and woodwinds.

From FSM comes a Goldsmith rarity, music from a short-lived TV series called Cain’s Hundred (1961-62), which starred Mark Richman as a former underworld lawyer who goes to work for the federal government determined to bring 100 top criminals to justice (thus: “Cain’s Hundred”). Goldsmith scored the pilot, opening two-part episode, and part of a fourth episode, along with the series theme; Morton Stevens, Fred Steiner, Jeff Alexander, and Harry Sukman scored the rest of the show; Stevens also revised and extended Goldsmith’s main theme for the final 8 shows of the series. It’s vintage television scoring, and it’s vintage Goldsmith. The main theme is a persuasive melodic progression – a melody for French Horn over a jaded, piping array of woodwinds and percussion below, written in the unorthodox time signature of 12/8; typically, Goldsmith provides an unusual change in direction at the end of the 20-second title cue, abruptly morphing from his steady rhythm into a very compelling angular ascension, a pair of howling cries culminating in a final downbeat, ending the provocative melody on dramatic leap. The series End Title slows the theme down and runs for just over a minute, which allows for some development and palette variation. The episodes occasionally refer to the title motif (the pilot cues “the Heist” and “Stella’s Death,” particularly, the episode main title pieces, cues coming back out of commercial), but otherwise consist of various motif fragments, set pieces, and unrelated cues. In addition to all of Goldsmith’s music from the show, the album includes 8 tracks from one of Morton Stevens’ episodes, including the new series title he arranged. The album closes with Goldsmith’s 7-second bumper, quickly terminating the episode vibe and allowing for a transition into commercial. Jon Burlingame provides vastly informative background information on the show, its cast, and its music.

Soundtrack News

Intrada released a limited edition soundtrack to Mr. Majestyk, the Charles Bronson action thriller written by Elmore Leonard (who novelized his screenplay). Intrada has released the soundtrack in a limited edition of 1200 units which have already sold out at the label. Also new from Intrada is a 3-disc edition of Carmine Copolla’s music from The Black Stallion, provided in both its album versions and its film version. Previously available on a 16-track release from Prometheus, coupled with Delerue’s The Black Stallion Returns, Intrada proffers

George S. Clinton has scored Mike Judge’s new comedy Extract, starring Jason Bateman, Mila Kunis and Ben Affleck. The film, which opens in select theatres on September 4, is a comedy about a flower-extract plant owner contending with an avalanche of personal and professional problems such as his potentially unfaithful wife and employees who want to take advantage of him.. For Extract, Clinton recorded a quirky and playful score to compliment the comedic style of the film. He used a small ensemble including guitar, mandolin, solo cello, pedal steel, and various percussion (also including the sounds of people playing actual extract bottles). The score was augmented by a chamber size string orchestra. Clinton also recently reunited with director Michael Lembeck (Santa Clause 2 & 3) for the comical-fantasy Tooth Fairy,starring Dwayne Johnson, Julie Andrews, Billy Crystal and Ashley Judd. Tooth Fairy will be in theatres February 2010.

Kritzerland offers a pair of never-before-released on CD soundtracks on one CD – Gaily, Gaily, music composed and conducted by Henry Mancini and The Night They Raided Minsky's, music composed by Charles Strouse. The former is Norman Jewison’s 1968 film version of Ben Hecht's fictional memoirs about coming of age in 1910 Chicago, and his beginnings as a journalist and author. The film was directed by and starred Beau Bridges, Brian Keith, Melina Mercouri, Hume Cronyn, and a very young Margot Kidder. Henry Mancini provided the absolutely delightful score. As was his wont back then, the album was a rerecording – it contains all the film's themes, but not the actual film tracks. The movie's main theme, "Tomorrow Is My Friend," is one of Mancini's most beautiful and haunting melodies - it's heard here in several variations, including a beautifully sung version by Jimmie Rodgers (the lyrics to this and the film's other songs are by Marilyn and Alan Bergman). The album also included a recitation by Melina Mercouri, accompanied by Mancini's underscore. As always, Mancini's music is tuneful, memorable, and altogether wonderful.

The Night They Raided Minsky's is the story of an innocent Amish girl who comes to New York in 1925, gets involved with a burlesque troupe at Minsky's Burlesque, and inadvertently ends up inventing the striptease. The film was directed by William Friedkin (his second picture), and starred Jason Robards, Norman Wisdom, Britt Eklund, Bert Lahr, and Harry Andrews. The score was by Charles Strouse, who'd had a big success on Broadway and would go on to score Bonnie and Clyde. With his lyricist, Lee Adams, he wrote several really clever and catchy songs for the film, as well as a bunch of clever and catchy themes to go with them. It's a wonderfully melodic score, and features vocals by Rudy Vallee, Dexter Maitland, Lillian Heyman, as well as the film's stars, Jason Robards and Norman Wisdom. It's a tuneful, toe-tapping, and terrific double bill. The latter film was also noted for having a splendidly detailed poster and LP cover painting by Frank Frazetta (pictured).

Kritzerland has also just released on CD the Neal Hefti score for How To Murder Your Wife, back in the day when infidelity and spousal murder comedies were all the rage. It was previously reissued for the first time on FSM’s expensive MGM Soundtrack Treasury, now sold out; it’s available singly through Kritzerland, which has also included Hefti’s unreleased on CD score to Lord Love A Duck.

Varese Sarabande has issued Brian Tyler’s score for Final Destination, the third film in the popular franchise. The first two were scored by the late Shirley Walker. Varese also has Nathan Barr’s True Blood and John Frizzell’s Whiteout coming up for September 8th, and the US release of Alexandre Desplat’s Coco Before Chanel (already issued in Europe and online digitally) on Sept. 15th.The World Soundtrack Academy has announced the list of nominees for the three principal categories in the World Soundtrack Awards, the pre-eminent international prizes for the recognition of film music: Film Composer of the Year, Best Original Score of the Year and Best Original Song Written Directly for a Film. The names of the winners will be proclaimed on Saturday, October 17 at the closing event of the Ghent (Belgium) International Film Festival.The World Soundtrack Academy. The Academy, which was founded in 2001 by the Ghent International Film Festival and a number of film music composers, now encompassing close to 300 leading composers and representatives of the film music business. The stated goal of the Academy is to promote music in film, and it is achieving this with ever greater success, as can be seen by the growing (international) interest and recognition being given to film music.

The nominees the World Soundtrack Awards 2009:

FILM COMPOSER OF THE YEAR

- CARTER BURWELL (Burn After Reading, Twilight)

- ALEXANDRE DESPLAT (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, Coco Avant Chanel, Largo Winch, Cheri)

- DANNY ELFMAN (Milk, Taking Woodstock, Notorious)

- MICHAEL GIACCHINO (Star Trek, Up, Land of the Lost)

- HANS ZIMMER (Frost/Nixon, Angels & Demons, The Dark Knight)

BEST ORIGINAL SCORE OF THE YEAR

- BURN AFTER READING by Carter Burwell

- THE CURIOUS CASE OF BENJAMIN BUTTON by Alexandre Desplat

- FROST/NIXON by Hans Zimmer

- THE INTERNATIONAL by Reinhold Heil, Tom Tykwer, Johnny Klimek

- SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE by A.R. Rahman

BEST ORIGINAL SONG WRITTEN DIRECTLY FOR A FILM

- “GRAN TORINO” from ‘Gran Torino’

- “JAI HO” from ‘Slumdog Millionaire’

- “O SAYA” from Slumdog Millionaire’

- “RUN & HIDE” from ‘Je l’aimais’

- “THE WRESTLER” from ‘The Wrestler’

Games Music NewsBAFTA award-winning composer Jason Graves has created an original music score for the intense first-person shooter Section 8 developed by TimeGate Studios. Renowned for his cinematic and prolific orchestral music on video games such as Dead Space and the Star Trek franchise, Graves delivers what has been described as a powerful and anthemic score for Section 8 featuring vintage synth and guitar elements blended with orchestra to portray the futuristic, sci-fi setting of the game. Section 8 is being released by SouthPeak Games for Xbox 360 and PC on September 1st, 2009.

"Section 8 was a great opportunity to combine my three musical passions: orchestra, electronics/synths and guitars," said Graves. "It was so much fun playing guitar and tweaking my analog synths. I treated them as additional members of the orchestra, sometimes taking the spotlight and other times adding textural background."

Section 8 gives players unprecedented strategic control over the battlefield, employing tactical assets and on-demand vehicle deliveries to dynamically alter the flow of combat. Set at the crossroads of a growing insurrection among its colonies, Earth dispatches the elite 8th Armored Infantry to turn the tide. Utilizing advanced powered armor suits, these brave volunteers are the only ones crazy enough to smash through enemy defenses and drop directly into the battlefield from 15,000 feet, earning them the nickname "Section 8.""The music focuses on the two primary locations of the game," added Graves. "One is more orchestral in nature and the other has a hybrid rock edge to it. TimeGate gave me a lot of freedom to try different things - it was refreshing to experiment with such a diverse sound palette."

www.jasongraves.com

Randall Larson was for many years senior editor for Soundtrack Magazine, publisher of CinemaScore: The Film Music Journal, and a film music columnist for Cinefantastique magazine. A specialist on horror film music, he is the author of Musique Fantastique: A Survey of Film Music from the Fantastic Cinema and Music From the House of Hammer. He now reviews soundtracks for Music from the Movies, Cemetery Dance magazine, and writes for Film Music Magazine and others. For more information, see: www.myspace.com/larsonrdl

Randall can be contacted at soundtraxrdl@aol.com