|

Scoring John Ford: New Music for a Silent Classic

January 14th, 2008By Randall D. Larson

This week we interview composer Tim Curran, who had the opportunity to write new music for John Ford’s 1928 silent drama, Hangman’s House, when it was restored for inclusion in Fox’s massive DVD set, Ford at Fox. Tim describes his efforts and challenges on rescoring a silent classic, as well as his experiences scoring contemporary films like The Big Break and Maximum Cage Fighting. Our first column of the new year also features a huge assortment of soundtrack reviews – 16 in all, from Alien and The Blob to Treasured Island, Balls of Fury, AVPR, Dragon Wars, Darfur Now, National Treasure Book of Secrets, Odna, The Killing of John Lennon, and more. We also cull cyberspace for the latest film music news, take a look at San Francisco’s recent Miklós Rózsa Film Festival, and have a look at the Brian Tyler’s scoring extras on the new War DVD.

Tim Curran at the Hangman's House recording sessions (with contractor Joe Soldo in background). Interview:

Tim Curran Visits Hangman’s HouseThe current trend in providing newly-recorded and performed scores for restored silent films has resulted in several new scores for the big Ford At Fox DVD box set produced by 20th Century Fox and released last month. The massive 24-DVD box set containing two dozen classic John Ford films, from early silents to early 1950s classics, collects many hitherto unseen Ford classics, and several of the restored silent films in the collection have been newly scored.

Tim Curran wrote music for Ford’s 1928 film, Hangman’s House, an epic silent film, set in Ireland, that features John Wayne in his first-ever role – as an uncredited extra – as well as Oscar-winner Victor McLaglen. Curran composed over 70 minutes of music, from sweeping Irish-flavored themes and romantic melodies to playful counterpoint and modern motivic composition to help enhance the film’s dark, gothic scenes. Hangman’s House is available as part of the Ford at Fox collection, in a mini-set entitled John Ford’s Silent Epics, and as an individual single-DVD release.

Curran comes from a jazz and classical background, which has served him well over the last decade, during which he has been called upon to write everything from big-band jazz charts to Nashville country jingles, and from huge orchestral action cues to atmospheric soundscapes – and nearly everything in between. Several mp3 files of Curran’s music from Hangman’s House are included within the interview as samples of his score.

Q: How did you get the job to score the John Ford film, Hangman’s House, for the new DVD Release?

Tim Curran: Nick Redman, who was working on this mammoth Ford at Fox DVD box set, called me up and asked me if I'd be interested in scoring one of the early John Ford silent films – the "Silent Epics," as the set came to be called. I'd known Nick for several years, but we'd never worked together in this capacity. In fact, he'd never heard my music. But just by coincidence, he'd recently heard good things about me from a producer at Fox, whom I'd worked with. So he asked me, and I jumped at the chance. These opportunities don't come along very often.

Q: What challenges did this assignment pose for you? How did you determine your orchestral pallet and thematic approach to this score?

Tim Curran: Well, the biggest issue was that I only had three instruments: piano, flute and cello. Composer Christopher Caliendo, who himself was writing music for two of the silent films, was brought on earlier as musical director for the entire "Silent Epics" project, so he initially determined the instrumentation. I never felt like that instrumentation was written in stone, but his instincts were right for the Hangman's House mood, so I went with it.

So the challenge was to cover the entire dramatic arc of the film with just three instruments – and not wear out your welcome with it; keep it fresh, etc. You don't realize how many tools you have at your disposal until they're taken away. As I was spotting the film, I remember thinking, "How in the heck am I going to score a four-minute horse race without timpani? Without brass? What I realized at that point was that I was going to have to get intimately familiar with these instruments – particularly the cello and flute – much more so than I would if I were writing for them in a section context. I knew I'd have to get creative. What percussive noises could I make with the cello – not just col legno, I mean, anything and everything. And with the flute, the same thing. What effects could I write that would sound fresh and still fit the film.

I was fortunate to have first-call session players on the project: Bryan Pezzone on piano, Sebastian Toettcher on cello and Sheridon Stokes on flute. I pretty much knew how I was going to use the piano, but for the cello and flute, I met with Sebastian and Sheridon before I started writing so I could get better acquainted with the nuanced stuff I mentioned. That proved very valuable.

As for thematic approach, the film is set in Ireland, unlike the western landscape that most people might associate with John Ford. And it's very dramatic, with lots of dark, gothic imagery, and epic set-pieces. It's a really rich film. It just seemed to cry out for lots of themes and motifs, so I spotted where those were needed and started writing them. I tried to keep the Irish material simple and folk-like; then with the darker, more gothic content, I could get a bit more dissonant, but that was mostly in harmony and orchestration. The themes themselves were still pretty simple. Pretty.mp3

Q: Obviously scoring a silent film places an even greater responsibility on the composer than a talking motion picture – how did you deal with the unique needs of writing nearly continuous music?

Tim Curran: Well, yeah, you're right. On one side, I was like, "This is great! No sound effects, no dialogue, just music!" The other side was like, "This is hard. No sound effects, no dialogue, just music." One of the first things I felt, interestingly enough, was the need to clarify certain things. For example, the main hero character Hogan (played by Victor McLaglen) is introduced in the first scene. Then he disappears for awhile. Next time he comes back, he's in disguise, so as a viewer, you most likely don't know who this guy is when you see him again. And to me there was no point in keeping it secret -- it was just potentially confusing. And there's no dialogue to ever clue you in. So I intentionally wrote a simple heroic theme that could be used as a calling card for Hogan in the first act, and could also work more thematically throughout the rest of the film.

Another challenge is in the spotting: With wall-to-wall music, where do you get in and get out? Then you have to balance that against what will be best for the musicians. Maybe the scene is very long and the music needs to be complex; for the sake of what's best for them, I need to find a creative way to cut that scene into two parts.

Generally, there was a pretty consistent pacing to the editing -- scenes would fade up, last for three minutes or so, then fade out. In many cases, the spotting takes care of itself – the cue lasts for the duration of the scene. But, I had to be careful not to become too formulaic with that approach. After awhile it begins to feel fragmented. So sometimes I played through the fade to black and into the next scene. Those transitions really helped smooth things out. Simple.mp3

Q: How did you respond, musically, to John Ford’s direction and his character/story development in Hangman’s House? Were there any specific musical considerations taken into account because this was a John Ford movie – from a director with a great legacy of musical references ((i.e., folk music, etc.) in his later films?

Tim Curran: I joke that this was the best way to work with John Ford, who was notoriously difficult. The fact that he's dead meant that I had the best of both worlds: I was able to compose music to his brilliant filmmaking, without having to deal with him making me rewrite everything. Seriously though, as I composed, I tried to imagine John Ford listening to what I had written, and that helped me not to veer too far from what would have been appropriate in 1928 – though I wanted to make it just a bit more contemporary. I wanted to make it sound like it fit the movie but didn't have that expected "silent movie music" sound.

It'll never cease to amaze me – and this sounds obvious – how much easier it is to score a good movie than a bad one. In the case of Hangman's House, Ford's direction and story development made my job simple. Besides the need for a little clarity, like I mentioned, everything was already on the screen. So then when it comes to the music, a lot of those considerations were dictated by what's already there – the folk-like Irish flavor, the darker dissonance, the humor. I relied more on those things than any specific element from Ford's later work. Hogan.mp3

Q: You’ve had a vast experience with many different types of music in your career, from jazz to classical to country. You did these influences and experiences come into play with the score you would provide for Hangman’s House?

Tim Curran: That's a tricky one, because I can't pinpoint specific places in Hangman's House where I'd say I relied on any of that. Yet, like everyone else, everything I do is a result of all of those experiences. I can say specifically, though, that the Irish flavor of the score came much easier to me thanks to my upbringing. My dad's side of the family is very Irish, so I grew up with that music.

Q: Your first feature film score was a hitman comedy titled The Big Break. What type of music did this film require and what do you recall of this experience?

Tim Curran: That film covered a lot of different territory -- rock, jazz, orchestral. There was an over-the-top quality to the action, so I didn't want to beat it over the head too much more. I wrote it pretty straight, with the orchestra covering the action and romantic parts. Then there was some lounge jazz stuff, some of it source. I played saxophone on it, and I hired a brilliant guitarist, Fino Roverato, to play on it, too.

I remember that that film had one particular challenge: The filmmakers had temped the opening scene with a rock/pop song. It was for the main title and the end title, but as the main title song it had to crossfade into a huge orchestral build-up and hit, which I had already written. Turns out, at the end of post-production they found out they couldn't license the original song. So my friend David Levine and I (we have a band called Chip & Drifty) wrote a song and recorded it the next day. But because of the orchestral bombast I had already composed, the song had to be written in a specific key, and with specific timings. The Big Break sample cue

Q: What was your approach to scoring an action film like Maximum Cage Fighting? What kind of score and instrumentation did you provide for this movie?

Tim Curran: Funny thing is, I think that because of the title, people might thing it's a Ultimate Fighting Championship video or something like that, when in fact it's got plenty of drama to go along with the action. I wrote that score with a composer friend of mine named Perry La Marca. After we spotted the film, we realized that the easiest way to do this in what little time we had was to split up the cues based on themes. So I took the "bad guy" and "training/fight" music and Perry took the drama/romance material. There was a little overlap, but that's how it was for the majority of the film. Maximum Cage Fighting sample cue

The orchestra was prominent throughout the score. For my part, I got to add some cool evil stuff – a low G harmonica, some slide whistle effects. The main theme for the bad guy was played on electric guitar, but I didn't want it to sound like every other electric guitar bad-guy theme, so I played around with the harmony under a very simple three-note figure. As for the training music, I channeled a bit of Rocky into a mixed-meter theme, which was a lot of fun to write. I used that for the more rock-oriented training scenes, and for a big orchestral cue in the final fight scene. Maximum Cage Fighting sample cue 2

Q: You’ve also scored several documentaries like WWII and the Home Front, General Frank Armstrong, Memories of Twelve O’Clock High. What were the musical requirements – and challenges – of these projects?

Tim Curran: Those documentaries were great to work on because I was able to write some old-style war-movie music -- big, bold, patriotic themes, etc. Also plenty of emotional understated stuff, too. In a way, documentaries represent the polar opposite of the Hangman's House situation, where the music is so present. In documentaries, you'll likely have a few brief scenes where the music can really shine (where the bold, orchestral palette is appropriate), but you're also writing under tons of dialogue. Some composers hate writing under dialogue because their music gets buried, and I understand that. But I really like it because it tests my ability to write with subtlety. And in documentaries, that's key. It's so easy to go over that line, and if you do, the music can take the audience right out of it. Memories of Twelve O’Click High sample cue

Q: What do you have lined up for the future? Where would you like to be in another few years?

Tim Curran: Right now, I'm working on a lot of commercial work for Disney, and I have another major advertising project in the works – a series of animated TV spots.

A few years from now, I'd like to just be doing more of the same kind of work I'm doing now – on more long-form projects, whether for TV, film, video games, it doesn't matter. I definitely want to work with more live orchestras and more live ensembles in general. There's just nothing like it, especially after having spent so much time working alone, composing for a particular job – to see and hear talented players bring the music to life. It's a great reward.

Soundtrack Recommendations

Jerry Goldsmith’s magnificent score for Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) has gone through a number of guises as a soundtrack recording. In the film itself, the music was repositioned, cut, and replaced with new music (most famously, three cues from Goldsmith’s 1962 drama score, Freud, and the inclusion of a segment from Howard Hanson’s Symphony No 2 heard under the closing titles). A 2000 DVD release of the film contained isolated music tracks – but, obviously, these were the final film tracks, barely resembling Goldsmith’s original recording. On record and CD, Goldsmith’s Alien score fared a little better. The original LP soundtrack, issued by Fox, gave listeners a sampling of Goldsmith’s original intentions that they didn’t hear in the film. The LP was reissued on CD several times, mostly recently by Silva Screen in 1988. Aside from a couple of bootleg releases, the new 2007 double-CD release of Alien is the first soundtrack to truly represent Goldsmith’s original, masterful composition (the score’s history is well documented on the CD’s informative and thoroughly analytical booklet notes). Culled from an original multi-track source discovered by 20th Century Fox, Intrada’s first disc contains the complete score as originally intended by the composer, 23 tracks and 57:06 mins, along with seven cues rescored during the film’s re-editing process. The second disc contains the 10-track original 1979 soundtrack album tracks, as well as seven demos and alternate takes. This is the definitive Alien soundtrack album that Goldsmith and sci-fi fans have been waiting for, and it is a brilliant restoration of a masterful composition. The score bristles with suspense and apprehension, while Goldsmith’s primary motive, a solo trumpet (and later violins and French horns) performing repeated patterns suggestive of the cold isolation and solitude of space, and a whole arsenal of unusual instrumentation, much of it fed through an echoplex to give it a warped effect. A rhythmic undercurrent of menace resonates beneath many of the cues. The music is full of odd phrases and phrasings, stingers and warbling ostinatos, and such provocative instruments as conch, serpent, Japanese gong, electric piano, vibraphone to give the score an unusual timbre and express the film’s alien environment. One of the score’s most remarkable unused cues is “A New Face,” an atonal and minimalist sound design as the Nostromo’s astronauts enter the alien hatchery and Kane is attacked by am embryo that leaps out of one of the many eggs found inside. Goldsmith’s approach here is amazing and fascinating, using high end harp notes and violins, distorted through severe echoplex; a pity this amazing cue was never used in the film. Likewise Goldsmith’s original End Title, which presented a fully developed, majestic statement of the main theme that grows to a joyful climax of triumph and survival. Intrada’s restored soundtrack permits Goldsmith’s composition to be revealed and appreciated for the brilliant masterwork it is. A sonic cornucopia of sounds and textures and rhythms and motives, Alien can finally be appreciated as it was originally intended, at least musically.

And if no one can hear you scream in outer space, try screaming while being smothered by a huge, gelatinous blob while sitting in a movie theater. The Blob charmed audiences in 1958 as one of the first teenager oriented science fiction films in a trend that lasted through the mid 1960s or so. Steve McQueen, in one of his first starring roles, leads a pack of well-meaning teens to destroy the amorphous blob creature when the adult authorities either refuse to believe it or behave incompetently in defending small town American against its onslaught. The film is best known for its cute novelty title song, written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David and sung by a concocted group called The Five Blobs. But the film’s underscore is a thrilling orchestral score written by Ralph Carmichael, later known for his work with the Billy Graham Crusade and in contemporary Christian music, although his career included much work in jazz and television. Finally released on CD by Monstrous Movie Music, Carmichael’s score for The Blob finally receives its due with a wonderful soundtrack release, presenting 28 tracks with 32:38 minutes of music. As producer David Schecter notes in his thoroughly analytical notes, the film’s popular novelty song, while ensuring the film’s success, implied that the movie was a comedy. “Had the picture been released with its working title, The Molten Meteor, and without the title music, chances are its reputation as a horror film would be far stronger than it is today.” As it is, The Blob is a powerful and entertaining science fiction thriller, with a straightforward orchestral score that is by turns thrilling and romantic. Restricted by the budget to 27 players, Carmichael emphasizes his string section to good effect to create romantic moods and to emphasize the rural desert in which much of the film takes place; the smaller brass and wind sections are mainly used to emphasize suspenseful moments and sudden shocks. There’s no real theme to the score, instead and appropriately Carmichael’s musical design shifts and flows and oozes much like the titular creature itself. MMM’s soundtrack is filled out by another 38:50 minutes of music culled from “The Valentino Production Music Library,” a collected assortment of library tracks which was licensed for use in any number of low-budget films in the 50s and 60s. The efforts of Angelo Franceso Lavagnino, Mario Nascimbene, and others are represented in the library, with music that was tracked into in such films as The Green Slime, Terror from the Year 5000, and The Brain that Wouldn’t Die. Schecter’s encyclopedic notes inform us of when and where these cues were used in these films – and why (i.e., the American release of Toei’s The Green Slime – an appropriate pairing with The Blob! – dispensed with composer Toshiaki Tsushima’s original Japanese score in favor of library tracks such as composer/arranger Roger Roger’s spacey tonalities. The same composer’s intriguing cues found their way into numerous other sci-fi scores to great advantage). The CD is concluded by a trio of source music tunes and one alternate take from The Blob. This is a delightful encounter with low-budget 1950s film music, preserving music I never thought I’d hear outside of the late late show bookended by used car dealership ads. Many thanks to MMM for their continued commitment to preserving and restoring vintage science fiction and horror film music from the 50s and 60s.

Chris' Soundtrack Corner of Germany has released the world premiere of the complete and remastered score of The Big Game (aka La Macchina Della Violenza), by Francesco De Masi. The film was a 1972 Europspy thriller starring Stephen Boyd, Cameron Mitchell, and Ray Milland, about corrupt world powers vying for possession of a strange device which can control men's minds. Featuring a trio of sublime early 70s europop songs performed by vocalist Melody, the score incorporates the songs instrumentally to find effect, whether in lounge music style as in “The Night is Ours” and “Daylight in Tight,” or speeded up into a rock setting, as in “Unveiling the Plot.” There are also more atonal moments (“The Sound from Space”, an eerie electronic and textural evocation of outer space), a cool pop tune with Asian colors (“Hong Kong Promenade”), 007-esque suspense passages (“You’ll Kill Her,” “Death Must Wait,” “End of the Dream”), rocking instrumental tunes (“Time Against the Run”), lush romantic melodies (“No War, Please”), and mesmerizing jazzified riffs (“Cape Town Harbor”). There are also two bonus tracks taken from album versions of the main themes, and two tracks of music that was not used in the film (one of which, “The Blue Boat,” is one of the score’s best tracks, with woodwind melodies over a harsh, fuzzy electric bass riff and an electric rhythm guitar, accentuated by punches of brass. The CD comes with an 8 page full-color booklet with liner notes by John Bender.

Nicholas Dodd is perhaps best known orchestrating and conducting all of David Arnold’s famous scores, including Stargate, Independence Day and all the four latest James Bond scores. But he’s also a composer in his own right, and the huge orchestral score Dodd composed for the French-British adventure comedy, Treasured Island (L’Île aux trésors) – his second film composition, following 2006’s action fest, Renaissance – has been released as a digital download and limited edition CD soundtrack from MovieScore Media. Performed by The Philharmonia Orchestra of London, the music is rich and potent, and Dodd proves to be a capable composer in large form scoring. The grandiose score is a thoroughgoing swashbuckler, a melodic amusement with moments of severe passion; lavish melodies, intricate filigrees, and large, complex orchestrations abound, built around a stalwart main theme that is reprised heroically on several occasions. But for all its bluster and bravado, Dodd does not lose site of the human factor, and he frequently waxes eloquent with intricate poignancies that are just as compelling and expressive as his larger themes. Treasured Island is a thorough winner, and one of the liveliest scores MSM has yet issued. Bravo!

Randy Edelman continues to be one of Hollywood’s most underrated yet consistently effective composers. His score for Underdog came out on iTunes recently and is a completely enjoyable heroic comedy score with Edelman playing straight man to Shoeshine’s doggedly heroic antics. Likewise Balls of Fury, his music for the entertaining kung-fu/ping-pong comedy that Varese Sarabande released on CD recently. Edelman writes simple scores that are melodically compelling and very accessible and I’ve always really enjoyed his work for its easy melodies and honest expressiveness. His music for Balls of Fury opens with a slight Asian tinge with “History in a Paddle,” emphasizing the nobility of the game. Out of this emerges a beautiful main theme for strings and sampled choir, driven by percussion in rather typical but extremely effective action movie style. “Shock from an Eastern Bloc” provides more hybrid action scoring, while “Training Shakedown” covers the film’s inevitable montage sequence, with severe synth chords slapping against a fast-paced percussive beat in a very Asian sounding cue. Edelman’s main theme takes on a number of guises, from the gentle Chinese ballad of “A Harsh Ballerina” to the poignant flute and guitar soliloquy of “Reflections in a Glass Pool,” and its many heroic measures reprised in “Sweet Victory,” “Statesman Feng Makes The Intros,” and “Little Girls Don’t Cry,” where it is given its summation from synth-choir and full orchestra over a pounding rhythmic river of drums. “Cracking the Ice” is a very nice romantic melody, gentle measures of winds over Asian strings and electric bass. “Derailed” is rich in orchestral flourishes of menace and danger, while “Pong the Swords” is the film’s climactic battle moment, splendidly accompanied by Edelman’s melodic flourish and energy. A very likeable score.

Varese Sarabande has also released Brian Tyler’s score from Alien Versus Predator: Requiem. It’s a harsh score, as one might expect, lots of dissonance and crashing chords, superlative horror-action material. May the assault begin: Tyler starts out with a pounding, booming, orchestral battery of percussion and brass set to full stun, and only rarely lets up. But, like Harald Kloser before him in the first AVP, Tyler allows an element of melancholy and humanity to emerge amidst the din. In Tyler’s case, it’s in the rhythmic violin melody that courses amid the snare and cymbal and brass of “Requiem Epilogue” (presented as track 4 on the CD; the CD does not appear to follow film order). In the 13-minute “Taking Sides” is a terrific journey through action and eloquence, culminating in wails of freight train horns, clubbing strokes of strings, piping brass and winds, slamming percussion. The score is awash in menace and violence, the listener assaulted on all sides in a fury of sonic claustrophobic terror, the music incarcerates the listener as alien entities wage war around us, their wicked battling choreographed by tremendous surges and flavorings in Tyler’s score, with both follows and leads the action. The small town upon which the alien and predator war infests itself is represented with gentler string music, such as “Kelly Returns Home,” but these moments, at least on CD, are few. “Striptease” is a moment of respite amid the chaos; a gentle synth, percussion, and guitar soliloquy, warm and expressive. But such moments are few and quickly overwhelmed by the aggressive energy of the alien war music. The dark, reverbed, and percussive tonalities that writhe below the orchestra in “Coprocloakia” provide a haunting sound design; they also fit the overall textural mood that links the Alien and Predator films and their music (some elements of the AVPR score are, indeed, taken from Alan Silvestri’s original Predator score – credited as such during the film’s End Titles; which gives the music an organic pedigree clearly linked to that of its progenitor); at the 2-minute mark in the same cue, Tyler inserts a series of compelling violin figures, developing them into a sobering heroic motif, but even this is soon crushed by another onslaught of alien combatants. “Down to Earth” reprises this motif anew, momentarily, but it’s the alien attack music that ultimately permeates the cue.

For another fascinating listen to Brian Tyler, Hollywood’s Master Musical Chameleon, check out his score for Finishing The Game, available as a download on iTunes. The film is a comedy that postulates what might have happened after the death of Bruce Lee, as studio execs and technicians try and complete his unfinished last film, Game of Death. It’s an interesting historical fantasy, and it has given Tyler the opportunity to concoct a delightful score brimming with 1970s funk. The score’s an instant time ticket back to ‘70s urban film music, the kind of stuff that we heard in a lot of the dubbed and Americanized versions of those Shaw Bros classics, not to mention the blaxploitation movies that were playing in many of the same theatres. The wah-wah guitar, flute interlude, quick-piping horns, and rich electric rock fluidity of “Golden Gate Guns” give it a great verve, while the funky country rhythm of “Real Deal” captures a drive and an energy that is equally compelling. “Ready or Not” is a cool rock-styled instrumental, while “Fists of Führer” (which wins the prize for cleverest cue title of the year) is brimful of R&B soul as it crafts a rhythmic propulsion of jangling electronic effervescence; horns over scratchy guitar, twangling electric bass, continuous beaten tambourine and occasional keyboard swirls and choral wails; the cue morphs into a straight-ahead profusion of rhythm, electric guitar and bass, keyboard, drumset, that speeds along on gleaming, lowridden wheels. While the score seems to be derived more from the R&B funk of the blaxploitation genre than what was heard in the original Shaw Bros films of the era (although many of these featured scores ripped off of any number of Italian and American films), it’s gives the film a groovy vibe, and a wondrous adventure in 1970s inspired action film scoring. Tyler’s score gives the film a unique and rather nostalgic musical sensibility, and an energetic drive and it works great on CD.

Dragon Wars (aka D-War) may be the dumbest excuse of a spfx fantasy to come along in a while, but it’s got a terrific score from Steve Jablonsky and that’s enough of a reason to pick up the soundtrack, issued in South Korea by Sony/Milan. I loved Jablonsky’s Transformers score, with its slow and majestic heroic theme, playing out over a slo-mo cadence that gave it an almost reverent power. Dragon Wars is very much along similar lines, opening with that type of motif for the Korean legend of Imoogi, which postulates the coming of a powerful dragon who can protect the universe – or destroy it. Jablonsky’s score has its basis in the same mythology that the film draws its story from, but where the film’s story quickly evaporates into nonsensibility, Jablonsky’s score retains its power and dignity, supporting the nobility of the dragon legend and the power inherent in the concept. The score demonstrates the story’s duality in its use of a subtle phrase from the Dies Irae (“Day of Wrath”) at the 4-minute mark in “The Legend Awakes;” the composer’s use of this medieval chant, which has found its way into countless horror scores from The Return of Dracula and The Screaming Skull in the ‘50s to Poltergeist, Conan the Barbarian, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and The Shining in more recent decades; even Jablonsky’s earlier Transformers used a variant of the tune represented the Decepticons, once more solidifying the connection between his Transformers music and this score; in “Village Attack,” Jablonsky develops the Dies Irae into a furious battle march. It will continue to represent the wicked side of Imoogi, whereas Jablonski’s main theme represents the nobility and promise of the “good” dragons. It’s not the most original approach (far from it) but it is effective and powerful and carries that automatic ”evil” reference that is thematically apropos. The score’s use of choir, while typical, gives the music an added power, as does the hybrid texture of symphs, synths, and samples, which gives the score a shifting and fresh resonance. “Village Attack” culminates in a powerful horn resolution that retains an almost epic quality in its sound. The main theme is transformed into a pretty love theme in, well, “Love Theme,” and a poignant variant is found in “Yeouijoo,” a pretty theme for winds under a blustery mist of hushed choir. “Hypnosis and Flashback” contains some cool atmospheric textures, and “Farewell” reprises the “Yeouijoo” and “Love Themes” in gentle measures for choir, piano and strings. A folk melody called “Arirang” concludes the score nicely. Somebody has posted a sample of the main theme at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_KzT6IxGsYc if you’d like to have a listen to it.

Graeme Revell’s score for Darfur Now, a documentary about the genocide occurring right now in Sudan's western region of Darfur, is out on Lakeshore records. The music is a very compelling fusion of ethnic textures and world beat/new age styled ambiances. It is very evocative in creating a sympathetic environment for the film’s depictions of what the filmmaker’s allege is “the worst crisis of the 21st century.” Revell sets down an effective and moving carpet of rhythmic atmosphere over which six intersecting stories describe what is happening in the region; the music is very persuasive and undeniably gives the documentary a tremendous power while also illuminating the human suffering and abandonment that lies behind the celluloid. The score’s power lies in its compelling musical textures and its sustained rhythms, both of which encourage repeat listening. If the music doesn’t inspire you to see the film, and if the film doesn’t inspire you to concern or action, at the very least it’s a very fine bit of music and one of the composer’s most interesting works.

Disney has released the music to National Treasure: Book of Secrets as a digital album available on iTunes. Trevor Rabin recreates his music from the first film with an appealing score for this sequel, opening with an intricate violin motif called “Page 47,” out of which emerges his heroic Main Theme, resounding mightily for orchestra and synths. It’s a short album, at only 8 tracks and around 24 minutes, but it’s an enjoyable score in the current vogue of hybrid action scores. Rabin constructs a powerful rhythmic motivic base and draws a lot of energy, passion, and jubilation out of it, which works well for the film’s preposterous but entertaining historical fantasy. A Parisian flavor sparkles on top of the action rhythms in “Spirit of Paris,” while the quirky “Bunnies” comprises a Thomas Newmanesque assemblage of mandolin-picked guitar, twanging vibraphone, and jingling bells, over a rising tide of synth/strings and slapping percussion. “Franklin’s Tunnel” serves as a fine climactic revisitation of the score’s elements, drawing to a furious and satisfactory resolution.

For those with more classically oriented tastes, Naxos has released a splendid world premiere recording of Dmitry (Dmitri) Shostakovich’s complete score for the 1929-1921 sound/silent film, Odna (Alone). With 48 tracks and almost of music, reconstructed by conductor Mark Fitz-Gerald and performed by the Frankfurt Radio Symphony with a trio of featured vocalists, this is the latest in Naxos’ line of ”Film Music Classics.” Odna was Shostakovich’s second full length film score, and one of his best. The film tells of a young teacher, eager to build a life of her own, who is sent to Mongolia to teach the children of the Altai shepherds, where she struggles against both elements and corrupt local politicians. Odna was initially designed as a silent film and only added music and a few lines of dialogue when sound came to the Russian studios, so the music takes on an essentially silent film role of supporting virtually all of the film’s activity through musical description (you can figure out the whole story simply by reading the cue titles). The music is impeccably performed. I’m not a big fan of opera, so the sung moments don’t do much for me, but the orchestral score is a sheer delight. There is a marvelous cue associated with the corrupt Village Chairman that resonates with evil wickedness: a lowly descent of wailing horns wavering languidly over an underlying march of low winds and strings until a counterpoint of higher violins funnels the cue into a severely dramatic and theatrical intonation. The motif recurs from time to time, and eventually plays off against the themes for the teacher and that of the villagers in the climactic “The Locals Express Themselves Violently.” Another cue, “Kuzmina Confronts the Village Chairman,” is an expressive cue that ends with a splay of what we have now come to recognize as Herrmannesque chords; one almost expects a Cyclops to come charging out of a nearby cave and attack the Chairman on the teacher’s behalf. This is a thoroughly compelling composition, wonderfully restored and performed. Score notes by John Riley put the music in its historical context and illuminate the development of the music.

New from Film Music Downloads is Martin Kiszko’s dark and ominous score to The Killing of John Lennon. The film, winner of the Special Jury Prize at the Tribeca Film Festival, was directed by Andrew Piddington (The Fall). Actor Jonas Ball won acclaim for his portrait of Mark Chapman, the man who killed John Lennon on December 8, 1980. The Killing of John Lennon is shot documentary-style with grainy photography and Kiszko’s atmospheric, and rhythm-laden score adds a strong and deeply emotional quality to the realistic pictures. Kiszko is one of England’s most prolific TV composers with over 200 scores to his credit, including The Uninvited, The Human Sexes, and Realms of the Russian Bear). The music is ambient and textural, conveying a dark psychological portrait of Chapman as the film details his activities prior to the shooting of the rock star. Kiszko uses a muted palette of piano, synths, and strings to craft his tone poem of Chapman’s disturbed personality. A solo soprano figures in “Headvoices” to emphasize the more disturbing aspects of Chapman’s growing delusions; a warm, almost heraldic melody for strings convey his arrival in New York City; a folk-based acoustic guitar motif escorts his visit to a gun store while haunting and echoed synths provide a nightmarish tonality for “Gun Practice;” A cool, rhythmic synth pattern grows in “Streetgirls,” providing an unusual human cityspace as Chapman wanders the streets, observing people and buildings (“Skyscrapers” are, in turn, evoked with a cool jazz piece); a compelling Eurostyled female vocal intones in “Subway Exit,” which closes the score with an air of melancholic resignation and sadness. FMD’s digital release of The Killing of John Lennon, with 27 tracks and almost an hour of music, is now available from iTunes or from www.filmmusicdownloads.com

A quartet of multiple-disc sets emerged during the holiday season that are also of note. Reprise Records massive four-CD set finally unveils the complete recordings of Howard Shore’s magnificent The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and concludes the annual box-set of Shore’s complete magnum opus. Shore’s three LOTR scores remain the finest film score of the last quarter century, in my opinion, and Reprise has done a huge service by providing them in such complete form. A 5th disc is again included with the entire score replicated in breathtaking 5.1 surround sound on DVD. The tracks are comprised and sequenced differently than in the original single-disc Return of the King soundtrack, so the box set complements rather than replaces the earlier edition. The music is sumptuous and intricately thematic, and Shore effectively wraps up loose thematic threads and beautifully supports the film’s multiple climaxes and conclusions. As with the previous two box sets, extensive liner notes, culled from Doug Adams forthcoming book, Music from the Lord of the Rings, provides illuminating and indispensable analysis of the score.

Sony celebrated the 30th anniversary of Star Wars with an 8-disc box set containing straight reissues of the original three soundtracks (A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi) provided in LP-facsimile paper sleeves. While the paper sleeves perfectly replicate the original editions of the three soundtracks, the CD content is, in fact, from the 1997 special edition releases of each score, with the additional material left off the original (and the 1993 “Trilogy” box set); see the fold-out “booklet” inside the box for the true track listing. Disc 7 consists of “The Correllian Edition,” nothing but a “greatest hits” version of cues from all six Star Wars films, which may make for a nice listen to segments of all six scores, although they are not collected in terms of thematic development or significance of the cue as it pertains to the series overarching musical development; it’s a fine collection of music but essentially remains rather pointless. The 8th disc collects the original LP packaging and inserts on CD-ROM, which also serves little purpose to the familiar listener. There’s nothing new, musically, to the set that wasn’t on the previous special edition releases, although the packing is quite nice if you’re as much into miniature LP sleeve editions as I am. But it’s a shame more new musical content wasn’t provided to make this a better value-added item for collectors.

Likewise, Disney’s holiday box set release, Pirates of the Caribbean: Soundtrack Treasures Collection, provides straight reissues of the previous trio of soundtrack albums with no enhancements except lovely packaging (a hardback book holder for each disc inside a sturdy box whose top lifts up to reveal the CD books housed within). In this case, however, we have a significant addition with a fourth disc, Remixed and Unreleased, that provides a small handful of previous unreleased or reworked material, plus seven pointless dance-style remixes of Pirates themes. But the unreleased tracks (culled from suites that Zimmer recorded during the scoring sessions to “warm up the orchestra” prior to recording specific cues against film) are quite interesting, including the orchestral version of “Hoist the Colors” from At Worlds End, Zimmer’s piano demo of Jack’s Theme from Dead Man’s Chest, a standalone version of Lord Cutler Beckett’s theme from At World’s End, and Zimmer’s first version of his Pirates theme that would later be adapted by Klaus Badelt in Curse of the Black Pearl, are all well worth having, even though a true “expanded” or “complete” soundtrack would have been preferred. There’s no new thematic material on disc 4, but the interpretations and performances are different from the individual soundtrack albums, and the disc makes for a great variation in listening and even a shortcut to enjoying the thematic variety of the Pirates music – at least until the House beat sets in on track 9. The 5th disc is a DVD containing a pair of documentaries behind the scenes; one an interview with Zimmer alone, and the other a filmed conversation between Zimmer, Bruckheimer, Verbinski and a large group of Zimmer’s musical staff chatting about their musical experiences over the three films (the docu’s attempts to become “artlike” by mixing color and black and white visuals, however, becomes annoying and self-indulgent after the first few monochromatic moments). Perhaps the most telling comment during this group discussion came from Disney’s President of Music, Mitchell Leib: “I think that because of the logistics and for the sheer reason that you [Verbinski] didn’t have the opportunity to temp it… listen to a lot of the movies that are out in the business. They all sound like it’s canned music – that’s because of the process. The process is, you temp it with some other movie score to get it to the road map, then you test the film, the film comes back high scoring, and then you end up telling the composer ‘hey, try not to mess with the road map!’ This thing, the logistics forced you guys to be completely, totally utterly original.” The group discussion, however, aptly shows how many people were involved in the music of the trilogy, from producer Bruckheimer, director Verbinski, and composer Zimmer to the many music editors, orchestrators, recordists, scoring mixers, soloists, additional music composers (Lorne Balfe, Geoff Zanelli, and Ramon Djawali), and conductors and other worker bees whose talented efforts contributed to the overall effect of these musical scores, and what a collaborative and intensive process film scoring is these days. The interviews last only about 20 minutes apiece, so they are far from definitive; we also have Zimmer’s 8:30 live performance of the Pirates Overture played at Disneyland for the world premier of At World’s End. Zimmer plays electric guitar and piano with a small ensemble of eleven players (2 celli, violin, electric bass, accordion, French horn, trombone, 2 drummers, 2 synth (the full orchestra either piped in or replicated by the synths – the musicians here are actually the main members of Zimmer’s music team, as he described in his solo interview; Balfe and Zanelli in drums, etc).

Finally there was the 3-CD 25th Anniversary soundtrack to Blade Runner, issued by Warner Bros to coincide with their spectacular 5-DVD box set of the latest “definitive” version of the movie. The “Trilogy” soundtrack includes the 1994 soundtrack album, which was the attempt to provide a proper release of the 1982 film’s music (the 1988 “orchestral adaptation” performed by The New American Orchestra for Full Moon records doesn’t count and needs to be forgotten). Disc 2 contains unreleased and bonus material provided here are the first time, while Disc 3 contains new music composed by Vangelis for Blade Runner’s 25th anniversary. There’s no real discernable relation between this new music and what Vangelis wrote for the film, so a more apt description of the third disc would be simply a new Vangelis instrumental album. But the new tracks on Disc 2, excerpted from the film soundtrack, are very welcome (take a cue, Fox and Disney!) with such atmospheric cues like “Dr. Tyrell’s Owl,” with its intricate electronic filaments chirping and hooting amidst a sea of synth undercurrent; the pulsating tonalities and aggressive chords of “Deckard and Roy’s Duel,” the moody chorale intonations of “Dr. Tyrell’s Death,” the brooding whimsy of “Desolation Path,” and the lullabylike “Mechanical Dolls.” Blade Runner was and remains a landmark electronic score (although it’s most significant theme is in fact performed on saxophone); Vangelis’ depth of electronic orchestration and his integration of the acoustic with the synthetic keeps the score fresh and provocative. The new material presented on Warners’ anniversary soundtrack adds to our appreciation of its brilliance.

San Francisco Festival Honors Miklós Rózsa

From December 26 through January 3, a unique festival was held at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco to honor legendary composer Miklós Rózsa (1907-1995). The festival, culminating a year’s worth of centenary tributes, was the first Miklós Rózsa film festival held in the US, celebrating the outstanding work of one of Hollywood’s greatest film composers, a three-time Academy Award winner who wrote 110 film scores between 1937 and 1981. “With a definitive, powerful, and unmistakably individual style, Rózsa’s passion and culture offer[ed] an exciting intensity to the medium of film,” noted the Festival announcement. “He virtually created the classic sound of 1940s film noir, and was the acknowledged master of the historical epic. As a brilliant composer for the concert hall, he represented a symphonic bridge between classical and film music, sharing his great talent with lovers of music on both sides of the artistic spectrum.” The festival was hosted by Castro organist and film music specialist David Hegarty, and featured onstage interviews with Rózsa’s daughter Juliet Rozsa, award-winning writer and film historian Steve Vertlieb, and Rózsa authority and orchestrator Daniel Robbins.

Reporting on the festival for the twitchfilm web site, Michael Guillen described the festivities during the festival’s opening screening of Ben-Hur, arguably Rózsa‘s finest film composition. “Among the tributes that Steve Vertlieb received and was asked to present was one by author Ray Bradbury who ‘adored’ Miklós Rózsa,” wrote Guillen. Vertlieb read Bradbury's tribute to the Castro audience and the Rózsa family members on stage: "In all my life I've never had a more complete relationship with a composer than with Miklós Rózsa. When MGM asked me to write the narration for King of Kings, I immediately joined a partnership with Margaret Booth, the film editor, and we became fast friends. The most wonderful moment in my life was when I went on the sound stage to watch Miklós Rózsa conduct the score for King of Kings and then heard my own voice booming out over the orchestra and dear Miklós' head as I spoke the narration. I wish that I had a recording today of my voice with his music because it became a partnership and a great friendship for life. To everyone hearing his wonderful music this week, I send my love and regard to the memory of Miklós Rózsa." Vertlieb likewise presented and read aloud an official proclamation in honor to the composer from the Ambassador of Hungary and the Hungarian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Seán Martinfield, the Fine Arts critic for The San Francisco Sentinel, likewise represented Mayor Newsome's office in presenting an equally fullblown proclamation from the City of San Francisco.

Guillen described Vertlieb’s telling a story that occurred during the recording of the soundtrack for Ray Harryhausen's The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. Rózsa complained at that time as well that the orchestra members were "lackadaisical" and didn't seem committed to rehearsal. Rózsa recounted to Vertlieb that one musician in the back row was reading a newspaper. He chastised the orchestra, "You all speak about religion and say that you're very religious. Well, music is our religion and you have to take it seriously." Unfortunately, the orchestra was thin and Vertlieb recalled that Harryhausen's co-producer Charles Schneer was a notorious penny-pincher who stood there during the recording sessions with a stopwatch. Whenever Rózsa wanted to do another take, Schneer would say, "No, no, no. That's good enough. Let's move on." This was, of course, a source of great frustration for Rózsa. Despite this, Ray Harryhausen adored Rózsa and they had a great working relationship.

Asked by Vertlieb to characterize her father, Rózsa's daughter Juliet remembered him "as a very European man, generous and humble." He traveled a lot. One of her most cherished memories was when she was 4-5 and allowed to listen to her father composing at home on his piano, which his contract with MGM allowed. Though his children were not permitted to be in the room while their father was working, she would nonetheless creep up the stairs, sneak quietly into the room and lie beside the family's pet boxer Mowgli underneath the piano. Her father would always find her and ask her to leave. She couldn't understand why she had to leave and Mowgli got to stay. A few hours would go by and the whole thing would go again with her creeping up the stairs and sneaking into the room underneath the piano with Mowgli, being found and asked to leave again. The house was always filled with music. Bizarrely, even when he wasn't home, she could hear his music throughout the house.

(- via http://twitchfilm.net/site/view/miklos-rozsaan-onstage-tribute/ )

Film Score News

Last night in Beverly Hills, the 65th Annual Golden Globe Awards were announced. Winning for Best Score was composer Dario Marianelli, for his music to Atonement. Winning for Best Song was Eddie Veder, for "Guaranteed," from the dramatic film Into the Wild. – via soundtrack.net

Upcoming Film Scores has reported that Tyler Bates (300, Dawn of the Dead, The Devil's Rejects) has been engaged to compose the original score for 20th Century Fox’s remake of the 1951 sci-fi classic The Day the Earth Stood Still. Keanu Reeves, Jennifer Connelly, and Jon Hamm stars in the film, which is directed by Scott Derrickson (The Exorcism of Emily Rose). The film is expected to premiere in December. The 1951 version of the film was directed by Robert Wise and featured a groundbreaking score by Bernard Herrmann. – via upcomingfilmscores.com

Fox’s new series, Terminator: The Sarah Conner Chronicles, debuts this Monday, and features original music by Bear McCreary (Battlestar Galactica, Eureka). The composer has scored the first nine episodes of the new show.

Brothers Jeff and Mychael Danna are scoring another two major feature films together in the near future. The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus reunites them with acclaimed director Terry Gilliam, with whom they worked on Tideland in 2005. Gilliam’s new film is another fantasy project, about a theater company that “gives its audience much more than they were expecting.” The Brothers Danna will also score the new Neil LaBute thriller, Lakeview Terrace, starring Samuel L. Jackson and Patrick Wilson. – via filmmusicweekly

Christopher Young has been hired to score another Hollywood remake of an Asian horror film, the multiple award-winning South Korean 2003 film A Tale of Two Sisters, which was directed by Ji-woon Kim. The US version is directed by Charles and Thomas Guard and produced by Dreamworks. Cast members include Elizabeth Banks, Arielle Kebbel, Emily Browning and David Strathairn. Christopher Young, who scored last year's number one movie at the US box office, Spider-Man 3, has recently scored thrillers Untraceable and Sleepwalking. The original version of A Tale of Two Sisters featured a score by Byung-woo Lee. – via upcomingfilmscores.com

Christopher Lennertz has scored the spoof comedy Meet the Spartans, the latest movie-satire comedy from the slaphappy minds behind Scary Movie, Date Movie, and Epic Movie. Meet the Spartans mixes 300 with films like Stomp the Yard and also features its share of celebrity bashing scenarios. The score was recorded in Servia with the Belgrade Film Orchestra using a 94-piece symphony and an 80-voice mixed choir and soloist. “I decided to take the score one step further and mix in sounds from around the world, even beyond the Middle Eastern elements that people would be expecting,” says Lennertz. “The lyrics being sung are based on a poem that I wrote after seeing the final cut of the film, and I had them translated into Greek. So when you hear a haunting wail floating above the lush orchestra chords, keep in mind that the words actually mean ‘Death by Penguin Testicles.’” The 20th Century Fox release comes to theaters January 25.

Jon Avnet’s new film, Righteous Kill, starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, is being scored by Edward Shearmur. The film is a crime thriller about two New York City detectives who hunt a vigilante who might turn out to be one of their own. Shearmur’s other upcoming films include Passengers, Bill and College Road Trip. – via filmmusicweekly

Gabriel Yared will compose the music for Adam Resurrected, Paul Schrader's new film, based on the novel by Yoram Kaniuk. It’s about a former circus entertainer who survived a Nazi concentration camp to work at an asylum for Holocaust survivors. – via upcomingfilmscores.com

Award-winning composer Jennie Muskett departs from her action and dramatic scores for Spooks MI-5 and The State Within to set a romantic yet dramatic tone to Miss Austen Regrets, based on Jane Austen’s own letters and diaries. The film, a co-production of BBC and WGBH, will be presented by PBS’ Masterpiece Theatre on February 3rd. The critically acclaimed mini-series The State Within, also featuring Muskett’s score, is currently nominated for two Golden Globe Awards. The score albums for both The State Within and Miss Austen Regrets will be released by Nicabella Records in February.

Rolfe Kent is set to compose the music for Seventeen, a quirky comedy about a man who suddenly becomes a 17-year-old high school student again. The film, directed by Burr Steers (Igby Goes Down), is set for release in 2009. – via filmmusicweekly

Soundtrack.net’s Dan Goldwasser has launched a new web site to house his many scoring session news items. The site will feature higher resolution imagery for almost all of the sessions previously covered at soundtrack.net, as well as additional photos not before seen – including sessions that were not covered previously. See: www.scoringsessions.com

Graeme Revell will return home to the world of horror when he scores the music for Australian-American genre movie The Ruins, directed by Carter Smith and starring Shawn Ashmore, Laura Ramsey, Jonathan Tucker and Joe Anderson. The film is based on Scott Smith's novel about a bunch of friends who embark on an archaeological dig in the jungle, discovering something evil that lives among the ruins. The film will premiere on April 8. - via upcomingfilmscores.com

Soundtrack News

This weeks releases from Varese Sarabande include Mark Isham’s persuasive score for The Mist, James Newton Howard’s score for both I Am Legend and The Great Debaters, and Marc Shaiman’s music for The Bucket List, the new Jack Nicholson/Morgan Freman comedy. (A song soundtrack from The Great Debaters is out on Atlantic Records, featuring a mix of newly recorded pre-1935 songs that were hand picked by Music Producer/Supervisor G. Marq Roswell and star/producer Denzell Washington for use in the movie).

Lakeshore has released the soundtrack to The 11th Hour, a cautionary environmental documentary along the lines of An Inconvenient Truth. Comprised of ambient tracks from various bands like Cocteau Twins, Sigur Ros, Triola, Deaf Center, Lamb, Mogwai, and others, the CD is an intriguing assemblage of ambient atmospheres.

January 31st will herald the 5th box set containing the complete music from the Godzilla films of the mid-to-late 1990s. Box set #5 contains nine total discs containing four soundtracks, Godzilla Vs Mechagodzilla (1993; Akira Ifukube), Godzilla vs. Space Godzilla (1994; Takayuki Hattori), Godzilla vs. Destroyer (1995; Akira Ifukube‘s final score), and Godzilla 2000 (1999; Hattori) plus two bonus CDs (Symphonic Fantasy and Ostinato featuring remixes and new arrangements). Still due is Box set #6, which should complete the series with the elegant monster scores of Michiru Ôshima from Godzilla vs. Megaguirus (2000), Godzilla vs, Mechagodzilla (2002), Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. (2003); Kô Ôtani’s music to Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001), and 2004’s Godzilla: Final Wars featuring music from classic rocker Keith Emerson.

Kenji Kawai’s soundtrack from the new Gundam anime series, Gundam 00, has been released in Japan on Flying Dog Records.

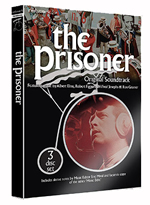

Due in late January, a 3-CD set containing music from the cult TV series, The Prisoner, will be released by Network Records. Compiled from the original master tapes by the series’ music editor, Eric Mival, the set will comprise the majority of music specially composed for the series (including a number of unused cues) presented in the order they were recorded. Complete with new notes by Eric which elaborates on his time on The Prisoner and a reproduction of his original music 'bible' giving an alternative and fascinating perspective of the production of the series, this new release is an essential purchase. Disc one features the original scores and themes for Arrival by Robert Farnon and Wilfred Josephs together with a selection of Ron Grainer's themes. Discs two and three includes completes scores for the episodes Degree Absolute, Play In Three Acts, The General, Free For All, Hammer Into Anvil, Face Unknown and Living In Harmony finishing with a few additional music cues for Fall Out. Content appears to differ from the music included in the 3-volume Silva Screen CD series released in 2002, and still in print.

Contemporary Recordings has released Trevor Jones’ complete score for We Fight To Be Free, a documentary film created for viewing at the Mount Vernon Visitors Center – not unlike Jones’ Gettysburg score, Fields Of Freedom, composed and released last year, a similar historical destination film that was created exclusively for a new, state of the art digital theatre near the Gettysburg Battlefield in Pennsylvania. We Fight To Be Free is the story of George Washington's most important military achievements and special personal moments of his life. The exciting score is performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. Also, Jones’ score for Tony Giglio’s 2005 thriller, Chaos, has been made available as an MP3 download from amazon.com and through iTunes. There are no plans for a CD soundtrack of this score, according to Jones’ web site (www.trevorjonesfilmmusic.com ).

Film Music Review has posted its list of the Best and Worst film music releases of 2007. See if you agree: www.americanmusicpreservation.com/best2007.htm

Daniel Schwieger has listed his own Best Scores of 2007 on page 7 of the current issue of Film Music Weekly. Download the pdf copy via www.filmmusicweekly.com

Film Music on DVD

Lionsgate’s DVD release of War, the Jet Li/Jason Stratham action thriller directed by Philip G. Atwell and scored by Brian Tyler, contains a significant number of features about the film’s score. In the 9-minute featurette, “Scoring War,” interspersed with shots showing the recording sessions with the London Symphony Orchestra, Tyler describes his approach to scoring the picture.

“Phil wanted to have a vibe that was hip and edgy, and made use of beats and all sorts of things,” said Tyler,“ but also he really wanted what we call a real “score” that had an orchestra and not [just] a series of songs that were unrelated. [He wanted] a score with themes and different motifs for different characters that could built dramatically throughout a film, so we thought it would be interesting to combine a lot of production like hip hop beats and electronica and garage and jungle beats and things like that with the London Symphony Orchestra – which was this clash of styles but we thought it would be interesting to go about it that way, and merge these two worlds.”

“I was very confident to allow him to go and do the things that he does without coming in early on and saying I don’t like this, I don’t like this, and kind of seeing where it could develop,” said director Atwell. War was his first feature film assignment, although he did second unit work on both National Treasure films and has a TV episode and several music videos under his wing.

“Because there [are] the triads and the yakuza and you’ve got the whole Asian influence, even though the movie [takes place] in the states, you wanted to bring that into the music,” said Tyler. “I had just finished scoring a film called Bangkok Dangerous [debuts Feb 17th, Pang Bros action film] as I was going to score this, and Tokyo Drift, so I was just I the mindset of doing movies that had a bit of Asian influence, so fortunately I was studied up on it, and it was something I had studied in college, I loved Asian percussion and Asian woodwind instruments, and we ought let’s bring that into the mix as well. Most of the percussion you hear in the movie, which is pretty predominant… was Taiko drums and a lot of Japanese and Chinese percussion. We wanted to use both to represent both sides of this war.”

Conducting the LSO for the first time, Tyler said, was also daunting when it came time to record the score. Knowing the orchestra’s history, from Sgt Pepper and Star Wars and beyond, Tyler wondered “what are they going to think of this music? They’ve heard all the greatest music, so for me getting up there to the podium and saying ‘let’s roll it on 4’ and there I go, it was insane! But an absolutely fantastic experience. They give so much me back to you than you give to them. You write the music out and you imagine in your head what it’s going to sound like and then they play it, it just blows your head off!”

Also, in a very extensive set of nine “The Art of War” featurettes that deconstruct the film’s major act onset pieces, Tyler is also well represented. Each segment examines the scenes in terms of story, style, stunts, and sound. Tyler explains very specifically his thought process and technique at scoring each of these sequences, including how he wanted to handle the plot twist reveal near the end, and how his themes played a part in establishing and accentuating that reveal.

Randall Larson was for many years senior editor for Soundtrack Magazine, publisher of CinemaScore: The Film Music Journal, and a film music columnist for Cinefantastique magazine. A specialist on horror film music, he is the author of Musique Fantastique: A Survey of Film Music from the Fantastic Cinema and Music From the House of Hammer. He now reviews soundtracks Music from the Movies, Cemetery Dance magazine, and writes for Film Music Magazine and others.