SOUNDTRACK GENRES |

| SHEET MUSIC |

| LPS AND CASSETTES |

| BARGAIN BIN |

| RARE AND ONE OF A KIND |

| AUTOGRAPHED CDs |

| NON-SOUNDTRACK CDS |

| RELATED LINKS |

| CONTACT US |

Past Columns

8/1/07

8/14/07

8/26/07

9/10/07

9/24/07

10/8/07

10/22/07

11/5/07

11/19/07

12/03/07

12/17/07

|

Soundtrax: Mark Isham and the Sonic Landscapes of Emotion

January 2nd, 2008By Randall D. Larson

This week we talk with Mark Isham about his latest score for The Mist, his first ever true horror score. We also chat about his approach to scoring Reservation Road, Crash, and Bobby. Reviews this week include Klute/All The President’s Men from FSM, Tales from Beyond from MSM, Trojan War/The Avenger and Morricone’s Men or Not Men from Digitmovies, and ponder the splendid gamescore from Mass Effect. We also take a look at the notable music featurette from the amazing Man From U.N.C.L.E. series dvd release from Time-Life.

A Conversation with Mark Isham

“To find the truth, you have to find who's hiding it.” In his score to Terry George’s Reservation Road, released on CD by Lakeshore Records, Mark Isham adopted a minimalist rhythmic ambiance that is dominated by keyboard, winds, and synths. The film deals quite directly with loss and grief, revenge and redemption as two families each cope with the loss of a child. As I noted in my review in my column for Oct. 22nd, “the score is darkly tinged, with a severe ambivalence of low synthnotes, rumbling tones, and electronic shards of sounds in low register. The tonality is appropriate and key to musically validating the emotions director George carefully instilled into his film.”

Q: I was very taken by your score for Reservation Road, which I felt was very Crashlike in its minimalist sensibility. How did you decide to approach this film and how would you contrast these scores?

Mark Isham: The movie was similar to Crash in the sense that it was highly emotional, and yet what was interesting about Crash was that the score had to float above the movie. That was my whole concept. The score really can’t get down into the trenches with these characters or it’s going to be overwhelming to the audience. That was my thought and Paul [Haggis; director-writer] agreed, so that’s how we developed it. One of the reasons the electronic medium seemed to work so well was that it did allow the music to sort of float. Reservation Road wasn’t such a stylized movie as Crash; it had a more of linear storytelling format but focused on very intimate portraits of these characters. You’re in their living room with them as they’re going through these traumatizing events, and once again I felt that the score shouldn’t overwhelm you or the characters or the story, it had to help you through the story, supporting both the characters and the audience. So I wanted to keep an intimate feel about it. But as we went through it, it also had to have some other bits. I think the Mark Ruffalo character was the most interesting, because there was a lot of emotion that was needed in the score for him that wasn’t necessarily shown directly on the screen. There was a lot of inner torment shown in a few scenes where we could establish that vocabulary and then we could come back and reintroduce that vocabulary and then you could feel, oh yeah, he’s just being torn up inside. I’m always interested in putting unique little ensembles together. The real instruments on this score were electric guitar, acoustic guitar, electric bass, bassoon, clarinet, bass clarinet, and alto flute, and six cellos, and there were a few electronic bips and baps.

Q: I think the Crash reference comes up because that’s become such an iconic movie for you, although actually it’s a style that you’ve had or a characteristic within your music, that goes back to Never Cry Wolf. You’re dealing with a very introspective approach, which is very emotional but it’s an emotion that doesn’t necessarily come out straight on the screen, it’s a subtext you’re carrying in your music.

Mark Isham: That’s a very precise connecting of dots there, because that’s exactly what I felt when I started Crash. I said, you know, I really haven’t done anything like this in a long time, and the last time I was given this free a reign was on my first score, which was Never Cry Wolf. Carroll Ballard was just totally open on that. He told me, “I hired you because of music of yours that I’ve heard and so you should do what you go.” He put no restrictions on me, and luckily, Carroll directs films a little like that; he likes letting a character sit there and letting the music sort of sit there with him, and, as you say, just be more introspective about everything.

Q: In Never Cry Wolf you seem to be scoring the environment the same way you would score the character’s inner emotions, as if you were merging the two. You’ve got this strange Arctic environment, and you’ve also got the soul of the character, almost as if there’s a duality there, and I’ve found the same kind of thing with Crash and Reservation Road, where the music is capturing and treating the emotions almost as you would an environment within which the music plays.

Mark Isham: That’s interesting. I can’t say that’s a big conscious decision on my part, but certainly, atmospheric music, ambient music, all those different types of approaches have always interested me. Pattern music, loop music, all sorts of things like that, definitely are a big part of my vocabulary.

Q: When you’re dealing with an ensemble picture like Crash or, perhaps to a lesser extent, Reservation Road, with a number of characters to keep track of, you seem to avoid providing a theme for each character in favor of a more atmospheric approach.

Mark Isham: I usually find that having themes for specific characters doesn’t help you out that much. Themes for relationships do, like the marriage, the mother/father that lost the child, their relationship, and then you’ll have a theme for the relationship between the two fathers, and then the relationship between Mark Ruffalo and his son. Of course, in a movie where there are only five or six characters, these themes also tend to be associated with individuals too, but the emotional quality of those themes comes out of those characters’ experiences, which is usually a relationship or one of the emotional themes of the film, like betrayal or trust or unrequited love or whatever; something the film is trying to convey and trying to lead you through. I find that using themes to connect those dots is emotionally much more effective.

“What has violence ever accomplished?” Isham’s music for Bobby, Emilio Estevez’s expressive examination of the shooting of Robert F. Kennedy in the Ambassador Hotel in 1968 and the people who were there that night, has been released by Lakeshore Records, and it’s a very affecting score. Isham favors his signature trumpet and, as noted in my review of the Lakeshore soundtrack album in my December 3rd column, “provides a respectful composition that not only honors RFK, but also evokes the humanity of the other characters through whose eyes the events of that early June 5th morning are seen.”

Q: That recalls another film you did recently and that’s Bobby. This also is an ensemble film and yet on top of it you’ve got that incredible sense of history – a recent history that many viewers can tie to a specific time in their on lives. What kind of approach were you asked to do on that film?

Mark Isham: The first thing that Harvey [Weinstein] said was “Oh, you can’t possibly hire the guy who did Crash!” And I phoned up Harvey, all ready to say, “Now, Harvey, don’t sell me that short! I’m not just going to write the same score!” He didn’t take the phone call but instead he hired me. It became very apparent to me very early on that that score needed to be very different from Crash, even though the ensemble nature was very similar, and that anything electronic was not going to help that movie at all. It needed to be big, have a slight epic feeling to it. It needed to be warm and orchestral, and then be able to go intimate at times, like that scene in the beauty salon. There were two scenes in the beauty salon that were just heartbreaking, and we strip it right down to piano and six strings or so. But when the chaos erupts in the kitchen at the end, that’s a big, sweeping orchestral ending, and it needs it. It’s of epic proportions, and you have Bobby’s famous words playing against it. You need that more traditional approach – a big theme and development of it, and that’s what we went for.

Q: What was most challenging for you on that score?

Mark Isham: The most challenging thing was that film changed a lot in the editing process. In fact it changed so much even after our first pass at scoring it; they went and recut the film and then we couldn’t use a lot of the music. The themes were right, but they were played in such ways that they slowed the film down now. Whereas before they felt at the right pace for the film, the recut made the film so much faster and so much more intercut, between all the varying scenarios, that I watched it and I went “oh my God, what have I done to this movie?!” But I realized, “well, it’s a completely different cut.” So we went back and rearranged the score. I rewrote two of the main themes with a conceptual change for the end. There’s a theme that starts right after the opening as Bill Macy enters the crowd during the fire drill, and goes all the way into reel two. There are some breaks in it, but it’s the same theme, and it was actually a pretty cool idea to connect all the various people you’re meeting with the same line, so that you don’t get thrown. You’re getting thrown a lot of different characters but let’s not throw a lot of different music at you; let’s keep the same musical mind all the way through, and I think it was pretty effective. That was a last minute idea.

Q: If you had too many themes the audience is going to get lost.

Mark Isham: Exactly. So we stated Bobby’s Theme in the introduction, and then sort of rounded that off, and then we started this, “Well, here we go now, folks, you’re actually not going to be with Bobby for a minute, you’re going to meet some interesting people.” And that carried you through until Bobby entered the picture again.

Q: It’s also almost as if The Ambassador Hotel was a character in the film…

Mark Isham: There was a point, actually, where I had an Ambassador Hotel theme!

“Fear Changes Everything.” Isham’s score for The Mist is all atmosphere and mysterioso. Isham accompanies virtually none of the characters in the film but rather musically confronts the malevolent outer-dimensional denizens that exude forth with the crawling fog that invades the formerly quiet Maine village. The soundtrack, which comes out on January 8th from Varese Sarabande, drifts almost imperceptibly through the film in small segments, angular shards of atonality and ambiance that give life to the unseen mist dwellers, and subtly enhances their grotesquerie when they attack. Isham’s music is shoved aside during the film’s second half, when repetitive needle drops from Lisa Gerard’s Dead Can Dance track, “The Host of Seraphim,” provide an eerie and evocative aria for the world within the mist.

Q: That brings us to The Mist, which is based on one of my favorite Stephen King stories. The film reunited you with Frank Darabount, your director on The Majestic. Coming into this film, what was your initial take on it and what kind of vibe did you get from the director?

Mark Isham: Frank had mentioned to me, a year ago, that he was doing The Mist, and I said, “well, obviously I’d love to work with you on it,” and he said “I’d love to work with you, but I’m not going to have any music in it, Mark. It’s all cinema verite. It’s all documentary style, we’re going to use sound effects and that’s it.” I said, “Well, God bless you, goodbye!” And then of course he sort of sheepishly called me about a month before the dub and said “I need some music!” But, on the other hand, he did spot it in a way which did keep a lot of his initial concepts intact. We only scored 18 minutes of the movie, and most of it, 95% of that, has to do with the creatures themselves –just adding to the chaos of the sonic element when the creatures are around. I tried to keep it completely atonal and just take one step above the sound effects in terms of becoming musical but not too much above them. I tried never to use a chord, only occasional intervals, and things like that. A lot of percussion, a lot of very modulated, discordant cluster things.

Q: Did Frank mention what changed his mind to make him realize, “ah, we do need music after all!”

Mark Isham: I think he just needed to up the ante. I think he found if you’re going to sit there for an hour and 35 or 45 minutes, you need the sonic landscape to change a little bit. In all the scenes, where there’s real dialog, where people are actually discussing things and intelligent and interesting and social commentaries are coming out and relationships are being explored, there’s no music. The music is reserved for, literally, “Holy shit! What is that! Oh no! Oh God! Aughh!” It is for when there’s nothing really, from a dialog perspective, worth hearing, and therefore the music has to fill in just the sonic landscape. I think it’s an interesting balance. I never saw it without it, he had actually temped in some things by the time I got there, to prove to himself that he needed me. It’s a good balance, because I think he still did keep his initial concept. On paper he has music but it certainly is not music in the traditional sense.

Q: Other than your score for The Hitcher in 1986, I don’t believe you’ve scored a full-on horror film like this. From that standpoint, and working with the mandate that Frank gave you, what was your take on music that would work for enhancing horror, suspense, shock, way beyond what you may have done on a more typical thriller?

Mark Isham: A lot of it was in the construction of the musical vocabulary – the decision to never be tonal, so that nothing ever was comfortable, and then to just not be afraid of going to real extremes, to just bang when you least expect it and hit a lot of things right on the nose, which you do expect, and then all the sudden doing something you don’t expect. Rhythm became a key element, because there was no such thing as melody you could rely on. There’s one motif and it’s simply based on a sampled string that’s being bowed and just got tweazed a particular way so that it’s half way between a mournful and horrific sound, but it feels completely organic at the same time. It was one of those great pieces of sound that you could just manipulate and use over and just twist it and get thousands of different uses out of. It sort of became the motif of the music, just this one moaning cry of despair, and you could use it against drums and be vibrantly alive, and you could use it by itself and just be petrified. And we actually found some great sampled voices of Bulgarian chanting and things like that. We tried to keep to things you don’t expect coming out of nowhere, just like the visuals.

Q: What do you have to go through to create sounds for a film like this, which in this genre seems to depending on new sounds that we haven’t heard before?

Mark Isham: It’s just fun for me to come up with all the knob twisting and the patch cords. I just dive in. I do it mostly in the computer now, but I have the same velocity. I’ll start with a sound that has the basis of what I want and just start twisting it around and tweaking it. The main thing, as I’ve mentioned, is to find something that I find has a performance element to it. If I’m playing around with a sound and I can’t keep myself amused with it, then I’ll generally throw it away and keep going until I find something else. The main sounds that are featured in this score were the ones that I could have played for a while. I improvised several pieces of music just based on these sounds; they’re so rich in their own make up that they’re just captivating, you’re just intrigued by listening to them.

Q: And how did you work with Frank during the process. How closely did he get involved in the music once you were brought onboard, especially given his original reluctance to use music?

Mark Isham: He left me along for the first couple of weeks, and then I had him come out and we went through it. He always has ideas, and expressed himself very, very well, actually. He will call up with new ideas, and have ideas right up to the last moment!

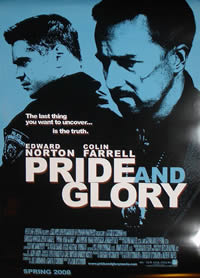

“We sold our shields off to the highest bidder.” Directed by Gavin O’Connor and opening next March 14th, Pride and Glory is a saga centered on a multi-generational family of New York City police officers whose moral codes are tested when one of them investigates a case that reveals an incendiary police corruption scandal involving his own brother-in-law. Isham’s score envelopes a musical Pandora’s Box that mirrors the revelatory drama that threatens to upend not only the family legacy but the entire NYPD. Isham completed the score earlier this year.

Q: How would your score on the forthcoming Pride and Glory?

Mark Isham: That’s an interesting movie. It’s a very dark but very richly emotional story. With actors like John Voigt, Edward Norton, Colin Farrell, you have these fantastic performances, and it was an interesting score in the sense that it may actually tie into a lot of what we’ve been talking about here. I wanted to be, at times, feel very epic, and yet at the same time Gavin wanted a very contemporary feel to it, but not in the sense that Bruckheimer type scores are contemporary and epic. Gavin was looking for something different, and I still don’t know if I can describe what it is because we had a hard time discussing it amongst ourselves while doing it. But just by trial and error we worked it out. There are melodies, but there’s a stark simplicity about them. In fact, one of the big motifs of the film is just four chords, and the four chords even change the voicing, so that the top voice is different. If you’re looking for a melody you won’t be able to find a consistent melody, and yet you always recognize the four chords, the way they move from one to the other,, and you always feel like you’re hearing a theme. Ideas like that took a while to find, as did, again, a very specific blend of acoustics and electronics. There’s a fair amount of music, I think 70 minutes of music and fifty percent of it’s orchestral but blended with various things, and a lot of drums. One of Gavin’s concepts on this movie was that there’s a war here, and at points the war drums have to come out, so that was something we worked on a lot.

Q: You worked with rapper Sage Francis on developing parts of the musical approach.

Mark Isham: That was one of the really fun things about that score. Gavin had the idea early on to have Sage Francis involved. He is a rapper, but he is a white guy with a background in political science who got so frustrated with the state of lyric in rap music that he said “I can do better than that.” He took off and has developed this really remarkable style, he’s just brilliant. And he’s like now a full-fledged rapper and does all the big shows and stuff. I mean, he’s still sort of underground in that sense, but he’s got a huge amount of respect in that community. And so Gavin wanted him to sort of narrate –we never could figure out just how to do that, but we ended up writing two or three things together, and one actually made it all the way to the end, and it closes the film. There’s no drums, it’s just classical acoustic guitar, orchestra, and rap. I’m really proud of it. It’s really fun, and that’s the balance of the score. It has that sort of cross breed feel all the way through it.

Q: You know, you’ve used the term “epic” a couple times here and I think that’s a telling concept in regard to some of the scores we’ve been talking about. Even in films like this, like Crash, like Reservation Road which, on the surface, aren’t the kind of films you would describe as being “epic” in nature, and yet the way you approach them and the way you are able to bring out the emotional level of the characters, I think there’s an epic quality in the way the music succeeds in doing that. Many of the films that you choose to score these days are those that have very deep opportunities for character growth, interaction, and comment from the music.

Mark Isham: That’s true, I mean, that’s what inspires me. I’ve done a lot of different films over the years, and this year I just had this tremendous opportunity to work on films that were very, very rich in their storytelling and in what they wanted to present, emotionally. So when I have these opportunities I just grab ‘em! Emotion is just a word for a category of lots of things – fear, triumph, and all the various things one can feel, so it’s very important to not get stuck in this thing of just feeling that “this scene has to be more emotional” because sometimes that just makes it gooey and too much of “I’m being pushed here and I don’t know what to feel and I don’t want to feel what I’m being pushed into” – you know what I mean? I think what I’ve learned over the years is that it’s very important to step back and ask, what is the emotion here? Let’s get really specific. Is this tragedy, is this sadness, is this despair, is this grief, because then the music can be really shaded to get it right, and when it’s right, that emotion just blossoms, and you feel all the more in those scenes. I mean, if you’re getting an epic sense of the music and emotion in a film even in these smaller films, that would be what I would offer as possibly an explanation. Just there’s been some really good homework done and discussions with the director, and a lot of the time when the director says “no, I just need it more emotional!” I say “don’t tell me that, that’s just like saying you need it louder! What are you really trying to say here? Where is this character really at? Have they lost all hope?” If we get it right, if we fine tune it down to what we’re really trying to say, then we can say it.

Q: It’s like, music can cover emotion and do it in ways that can be very syrupy or very phony or very trite, and yet you’re stepping back a bit and really seeing the big picture, as opposed to being so closely tied to the emotions and the tears or the rage or whatever it might be, but you’re looking back and commenting on, “here’s the subtext behind these emotions we’re seeing here.”

Mark Isham: Well, thank you. I like to think I get that deeply into it. I can’t always tell, obviously, by the time I’m done.

Q: What do you have coming up?

Mark Isham: Actually I have switched gears completely and I’m doing a Football movie, which is actually a lot of fun after I’ve had this year of tense drama! Not to say that this isn’t tense: it’s a very interesting story. It’s called The Express and it’s about the first black Heisman trophy winner [Ernie Davis], so it’s a big, there’s a lot of civil rights things in it. He’s the guy who took Jim Brown’s place at Syracuse University, so it’s got some interesting historical points of reference and just all around a very good story. Dennis Quaid plays the coach and Rob Brown is just fantastic as Ernie Davis. It’s been done real well, and it’s testing out the roof, I hope the studio gives it its just due. [Gary Fleder directs, for whom Isham has previously scored Kiss The Girls, Don’t Say A Word and Imposter.]

This Week’s Recommendations

The late Michael Small was one of the best composers for 1970s era thrillers, and 1971’s Klute was one of his best scores. Never given an official soundtrack release, it generated only a 500-copy bootleg LP in 1977, a CD bootleg a couple of years ago and transfer of that released by England’s Harkit label in 2006. As their Silver Age Classics release for December, FSM provides the first legit issue of Klute, adding ten tracks to the previous boots, and pairing it with an equally splendid unreleased 1970s thriller score, David Shire’s All The President’s Men. Both are must-have soundtracks from two of the decade’s best composers. As was Small’s penchant, the Klute score is a mix of minimalism and a kind of contemporary post-romanticism, blending a sultry trumpet love theme over an eerie percussive main title theme that features highly reverberated and processed bell, piano, and chimes; in later reprisals (“Phone Call Play Back”) Small adds an echoey female voice intoning in a manner not unlike that of Kryztof Komeda’s Rosemary’s Baby or Morricone’s Bird With The Crystal Plumage. “Goldfarb’s Office” also resembles vintage Morricone giallo, with a splendid zimbalom playing the melody over a gentle undercurrent of swaying swings and piano rhythms; a cool Godfather-like vibe is added when the strings take the melody into a slow waltz.

There’s also some cool late 60s/early 70s pop instrumentals such as “I Want To Speak with You” and “Walk to Casting Office” with lend a cool cultural/environmental vibe to the film’s period. “Casting Office” features a bizarre assemblage of sitar, ethnic flutes, and other exoticisms to proffer a mesmerizing and intoxicating ambiance that enhances more nightmarish elements of Alan J Pakula’s unique murder mystery. “Cable’s First Office” is a breezy pop tune, while “First Disco” and “Laguran’s Disco” (incorporating the song, “Take it Higher”) are pretty much what you’d expect it to be, electric source filler for discotheque scenes, although the rhythm section enhancement in the latter is quite persuasive and funky. But all of these diverse elements congeal very nicely into a unified whole consisting of three primary facets, as Kyle Renick describes in his excellent and analytical liner notes: “abstract avant-garde thriller underscore mostly featuring piano, percussion, and voice; a melancholy jazz/rock ‘love theme’ spotlighting trumpet; and source cues for the various urban environments.” This trio of motific elements contrasts and complements an overall sound design that is both uniquely 70s and uniquely fashioned to augment Pakula’s stylistic brand of post-noir contemporary psychological thriller.

Shire’s music for Pakula’s 1976 interpretation of Woodward and Bernstein’s chronicle of the fall of President Richard Nixon, All The President’s Men, is derived from similar cloth. A minimalist score built on vague melodies and consistent rhythms, the score’s central motif is a four-note figure presented in rising scales which provides both depth to the story and an ongoing sense of heightening mystery. French horn embodies the status quo – the government and the law as initially presented early on, while a chordal theme from clarinets informs the newsmen as they begin to investigate the corruption that will lead them to the top of the elements referenced by the horns. The music is both elegant and discomforting as these elements fuse and engage in conflict; Shire builds the score in jigsaw like pieces, adding elements here and there and not revealing his complete thematic composition until the very end. Listening to the score on CD is a revelatory experience as the score develops purposefully and compellingly.

Both Klute and All The President’s Men are outstanding scores and two of the milestones of early 1970s filmscoring.

MovieScore Media’s final release of the year is a splendid mysterioso – newcomer David James Nielsen’s classy orchestral score for Tales From Beyond, a 2004 Twilight Zone-ish anthology story comprising four macabre stories from a quartet of directors, built around tales of a bookshop owned by a shopkeeper played by Adam West. Nielsen, who got the plum assignment right after graduating from USC’s film scoring program (MSM has also released Nielsen’s subsequent score, Haunting Villisca), essentially provides four unique scores for each of the four stories embodying the film, plus the mysterious title, prologue, and finale music. A 5-track suite of jazz cues used in different episodes is also provided, making this a thorough and well-presented package of music. The overall tone is one of dark, mesmerizing, atmospheres, and Nielsen crafts these very nicely. “Abernathy” comprises a soft mysterioso, derived somewhat from Nielsen’s prologue, emphasizing finely echoed and intricate harp notes over strings and piano, enhanced by haunting voices in a vague air that is more atmospheric than melodious; “Theme” closes out this episode with a haunting articulation. “Nex’s Diner” takes on a prominent lounge-jazz atmosphere, appropriate for its setting (most of the source cues collected in the “Jazz Suite” are from this episode); Nielsen derives his suspenseful scoring from the jazz sensibility heard in the Diner, while “Life Replay” is accompanied by a series of quirky and experimental tonalities and musical effects, not unlike that often used in Twilight Zone scores. “Fighting Spirit,” on the other hand, is built from layers of ascending orchestra, very uplifting and emotional. While almost entirely devoid of melodic content, Nielson’s atmospheric quotient is effectively high and the diverse score is quite likable. And his “Finale” is a stupendously awesome and energetic dark climax to the quartet of weird tales.

Italy’s Digitmovies label has released a sixth volume in their series dedicated to the Italian Peplum genre, proffering the original soundtracks of two movies composed by Giovanni Fusco, The Trojan War (La Guerre de Troia, 1961), and its sequel War of the Trojans (La Leggenda Di Enea, 1962; aka The Avenger). Steve (Hercules) Reeves starred in both films as Enea (Aeneas), hero of Troy; the first was directed by peplum veteran Giorgio Ferroni, the second, unusually, was directed by American Albert Band (and featured his then-young son, now noted B-movie director Charles Band, as Eneas’ son). Both films were scored with thick-hewn orchestral and choral vigor by Giovanni Fusco, one of Italy’s most prolific composers of the 40s and 50s. The two cd-set contains the complete musical scores to both films, including a couple of alternate versions of cues from each. Fusco infuses both scores with elegant brassy fanfares and lots of choir intonation, which give the films an epic, regal splendor that befitted their lavish set design and epic intentions, while a gently pastoral motif for oboe and harp represents the film’s softer moment, as a love theme for Enea and his beloved, Creusa, often heard at variance with the heroic main theme, as Enea’s attention is diverted by the need for battle. A recurring challenge motif, introduced in “The Challenge,” scuttles along from winds and what sounds like pizzicato strings. The famous Trojan Horse is introduced with a solid fanfare of horns over swirling violins, driven on by beaten drums and a variation of the Challenge Theme taken by horns, climaxed by a lavish ring of cymbal. When the soldiers emerge from the wooden horse’s belly, Fusco reprises his Challenge Theme to accompany the hushed evacuation of the soldiers from the edifice.

Themes from the first film are not shared with the second film, which opens with a quasi-religious march motif and a variety of mysterious and ancient-flavored motifs presented as set pieces. The score features some splendid brass and woodwind piping, with some very exciting and sparkling cues. “To The Attack” is an excellent action cue that really gets going with a flurry of piping winds, stalwart horn inflections, clusters of skirmishing piano notes, opening into a furious aggression of full-on orchestral prowess. The “Finale” is an audacious concluding march, solid with brass and percussion, although much of its power is obscured by a flat monophonic recording.

These are both good scores, although Fusco’s orchestrations and the performance of the orchestra some times become fairly ponderous. Some cues tend to lapse into redundancy, built on repetitions of the same figures with little development, but often an intrusion of vivid orchestration will enliven these tracks, such as in War of the Trojans’ “Encounter Between Two Tribes” which emerges from a dull monotony at the 2-minute mark into a wonderful and exciting motif for muted trumpets and piping winds over timpani. Despite its occasional descent into the lackluster, these are both worthwhile scores. Digitmovies ongoing attempts to preserve the forgotten music from the musclebound “sword-and-sandal” era of Italian filmmaking are laudable.

Digitmovies has also unearthed a rare Morricone score, providing the complete original soundtrack from Uomini e no (aka “Men or not men”), a 1980 war drama directed by Valentino Orsini;. The film explores the Italian Resistance during World War II (a topic favored by the director, who was in fact involved in that resistance during the War). Only one cue from this score was released previously, on a 1981 compilation LP called Ciak; that track opens this CD, which presents it in an extended version. Morricone’s score emphasizes the human drama behind the actions depicted in the film, with lovely woodwind passages over the composer’s characteristically roaming piano, and severely passionate solo violin playing (“Enne 2 E Berta” is a standout track on the CD). This theme is contrasted against a militaristic march, performed in varying speed across the soundtrack, where it serves as an ostinato to remind us of the mechanisms of war in which we are enmeshed in this story. The brass and percussion cadence, which progresses attractively like most of the composer’s military marches tend to, embellished by flurries of flutes and illustrative textural augmentations, defines the strategic and tactical considerations of waging war (and defending one’s homeland against it) while the love theme represents the passions of the protagonist and his search for love in the midst of a terrible conflict. Flutes, oboes, harpsichord, and solo violin occupy the high ground in this score, which resonates powerfully and evocatively throughout. This is a thoroughly engaging score and a provocative musical examination of human passions and human conflict.

Mass Effect, the original game soundtrack composed by gamescore veterans Jack Wall and Sam Hulick (with additional music by Richard Jacques and David Kates), is about as epic as gamescores get – a magnificent and massive hybrid score rich in sampled orchestral and pure electronic textures. Released by Something Else music, the leading purveyor of video game soundtrack, it features a main theme reminiscent in its slow cadence and massive power that of Jablonsky’s Transformers or Kloser’s Alien Vs Predator. It’s a provocative main theme, energetic and propulsive, and instantly thrilling. The score carries a compelling mix of anthemic orchestral elements and rollicking rock cadences which beat out an incessant time signature prompting an urgency in gameplay. Nominated for Best Video Game Soundtrack (see Game Score News, below), this is a vibrant and energetic composition that can compete well with most any hybrid action film score. “The Wards” opens with cool synth atmospheres but soon emerges into a really neat rhythmic vibe as electronic patterns soar over an absorbing bluesy synth beat, a delicious fusion of orchestral sensibility with the organic tempo and beat of the blues. “Liara’s World” is an exotic assemblage of layered tones, quirky textures, and vividly growing synth gesticulations, a constantly swerving and squirming and colliding stew evocative of mystical environments. “A Very Dangerous Place” is brim-full with engaging texture-driven rhythms and dark, hollow, and echoey beats, a gloriously synthetic rendering quite the opposite of the attractive delight of “Liara’s World” but instead occupying a soundspace warning of doom and constant menace. With 37 tracks and more than an hour of music, there’s plenty here to inspire and savor away from the gaming console. The score is occasional reminiscent of the approach of Vangelis in Blade Runner, unabashedly electronic and yet with enough references to acoustic instrumentation to give it an organic sensibility even in the midst of its edgy synth textures.

Film Score News

Edward Shearmur is scoring Jon Avnet's new film, Righteous Kill, starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino. Shearmur also scored Avnet’s recent action thriller, 88 Minutes (he was also a producer on Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow). Shearmur's other upcoming films include Passengers, Bill and College Road Trip. – via upcomingfilmscores

Film music’s most intrepid interviewer, Rudy Koppl, provides excellent coverage of the music to The Golden Compass, Chris Weitz’s adaptation of the first volume of Philip Pullman’s theophobic fantasy trilogy, His Dark Materials, interviewing both composer Alexandre Desplat and writer/director/producer Weitz. Now posted at www.musicfromthemovies.com

Marco Beltrami has composed the music to The Eye, the Americanized remake of the Pang Bros.’ celebrated Hong Kong horror offering from 2002. Jessica Alba stars along with Parker Posey as a blind woman who begins, well, seeing dead people. David Moreau and Xavier Palud direct.

Alan Silvestri is attached to Stephen Sommers’ new action adventure, G.I. Joe, which is based on Hasbro’s line of action figures. The film follows the recent success of Transformers, which was also based on a Hasbro brand, and is currently in pre-production. The film will be released by Paramount in the summer of 2009. – via upcomingfilmscores

Rachel Portman will score The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants 2, the sequel to the 2005 film, scored by Cliff Eidelman.

James Newton Howard and Hans Zimmer will reprise their collaboration from Batman Begins when the reunite with its director, Christopher Nolan, to score the caped crusader’s next noir adventure, The Dark Knight, due for release in July.

Nicholas Pike, a veteran of horror films with such scores as Fear Dot Com, Sleepwalkers and the mini-series The Shining, is currently working on the score for the remake of Larry Cohen's 1974 genre classic It's Alive, which had featured eerie music by the legendary Bernard Herrmann. Pike also has the score for the horror film Parasomnia coming up. – via filmscoreweekly

Harald Kloser is scoring 10,000 BC, Roland Emmerick’s prehistoric adventure epic (think Ice Age, live action) which will hit screens in March.

Michael Giacchino is set to score Speed Racer, the eagerly anticipated new action film from Matrix mavens, The Wachowski Brothers. The film, which is scheduled to premiere on May 9, is based on the 1960's Japanese animated series about a young race car driver and his advanced car. – via upcomingfilmscores

Soundtrack News

Veteran composer John Cameron, who was nominated to an Oscar for his score A Touch of Class way back in 1973, has composed the stylish electronic score for David L. Cunningham’s horror film After... starring Daniel Caltagirone, Flora Montgomery and Nicholas Aaron. The story, about “Urban Explorers” who thrive on infiltrating a planet’s most dangerous man-made structures, prompted Cameron to create a score which makes use of eerie electronic effects and vocalizatons in conjunction with sparse solo instrumentation for piano, violin and flute. The music creates a unique atmosphere and also offers some intriguing action writing which is somewhat akin to the mid 80’s style of Jerry Goldsmith’s electronic film scores. Exclusively a digital release, After... is available from iTunes and Film Music Downloads.

For the first time ever, the complete Academy Award winning musical score to the 1951 Gary Cooper western classic High Noon is available on compact disc. The score, by Russian composer Dimitri Tiomkin, has long been a favorite of film fans and was the first major film to feature a title song as a ballad that is integral to the storytelling process. “Do Not Forsake Me” was sung on the soundtrack by Tex Ritter and won an Academy Award, in addition to the film’s thematic underscore. High Noon was an independent production, produced by Stanley Kramer, directed by Fred Zinneman, and released through United Artists. Through the years, while the film has survived, the ancillary negative elements – including the optical soundtracks containing the original music recordings – have been lost. However, a complete set of score recordings was kept by Tiomkin and it is these acetate discs that provided the audio materials used for the CD release. After being transferred to digital audio, the 55 year-old recordings were painstakingly restored by CR Studios and a symphonic representation of the complete musical score was produced. Screen Archives designed the lavish, 32-page full color booklet featuring original artwork and production notes by film historian Rudy Behlmer.

- via Ray Faiola www.chelsearialtostudios.comKnown for his score for the quirky TV series, Dexter, about a police investigator/serial killer, composer Daniel Licht now turns his attention to world of Cashmere Mafia, a new dramedy by Sex and the City creator Kevin Wade. Starring Lucy Liu , Frances O'Connor, Miranda Otto, and Bonnie Somerville, the ABC-TV series premieres Thursday, January. 3. The series will move to its regular day and time Wednesday, January 9. “It's a much lighter show, but interestingly enough, I found that my approach for the show was not terribly, terribly different than Dexter,” says Licht. “I don't want to give away much more than that. I had fun with the title 'mafia' and pushed it in that direction." Cashmere Mafia follows a group of successful female executives who have been friends since college who turn to each other for guidance as they juggle their careers with family in New York City. The premiere episode will be available on ABC.com the day after airing on the network for users to watch online.

Varese Sarabande will release Marc Shaiman’s heartfelt score for The Bucket List on January 15th; the film is a comedy starring Jack Nicholson and Morgan Freeman as geriatrics who meet in a hospital and decide to do everything they always wanted to do before they “kick the bucket.” The CD will also included newly-recorded themes (by Shaiman) from his previous film scores. Katherine Heigl’s next romantic comedy, 27 Dresses (she’s a repeat bridesmaid who falls in love with her sister’s husband-to-be) was scored by Randy Edelman; Varese releases the soundtrack on January 29th. Marc Streitenfeld’s score for American Gangster will appear on February 19th.

Sony has issues a lavish 3-disc set called Classic Cinema, comprising music from some of history’s biggest movies. Despite the attractive tri-fold digipack case and splendid presentation, the content is purely for non-collectors – those who don’t already have soundtracks to virtually all of the tracks included in Sony’s anthology: Superman, Platoon, Lord of the Rings, Gone With The Wind, The Mission yada, yada, and yada. The setlist is pretty much what we find in any recent film music collection, although Sony has given us a couple of lesser known treasures – Debbie Wiseman’s Arsene Lupin and George Fenton’s Stage Beauty to name a couple. This would be an ideal gift for the non-initiated and, coming out just prior to Christmas, may well have been the intention.

From Korea comes the soundtrack to Seven Days, a new thriller starring Yun-jin Kim (Lost), which opened in November. The score is by Kim Joon Sung, a renowned musical director who received a Blue Dragon Award for his work in Marathon (2005). The film, which centers on a lawyer who must free a convicted killer in just one week or else see her kidnapped daughter murdered, was recently picked up by Hollywood’s Summit Entertainment so look for an Americanized remake on the horizon.

From Japan comes a soundtrack album to the second anime feature based on the TV series, Bleach, The Diamond Dust Rebellion. The movie score is by Shiro Sagisu, known for his scores to Hideaki Anno's series Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Selected interviews from past issues of both Soundtrack! The Collector’s Quarterly and CinemaScore: The Film Music Journal, are being posted to a new web site at www.runmovies.be/ The site, hosted in Belgium, is in the French language but the SCQ and CS archival material is in English. Also, a few copies of specially reprinted CinemaScore back issues from the late 1980s can be found on sale at amazon.com (including a few original remainders of its last issue, 160-page #15).

Six tracks of Jessica De Rooij's elegant and heroic score for Uwe Boll's cyber-action comedy Postal are included on the online soundtrack, now available from iTunes. De Rooij has scored Boll's Bloodrayne 2 as well as his lavish heroic fantasy, In The Name Of The King, which like most of Boll's efforts is based on a videogame. The latter has been issued as a soundtrack CD by Nuclear Blast Records, although only two of De Rooij's score (and none of Henning Lonner's tracks from the film) are on the CD. The rest is a very good compilation of metal and progressive metal tracks from Nuclear Blast CDs that made their way into the film. If you like prog metal, it's a terrific compilation - but I'm waiting for a fuller release of Jessica's score.

Film Music on DVD

While the Time-Life exclusive 41-DVD special edition release of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. – The Complete Series, is a costly investment, it is by far the year’s most significant DVD release and a must have for any acolyte of the 60s who grew up with Solo and Kuryakin. Included in the massive set’s hours and hours of exclusive extras is a cool 23-minute featurette called “The Music of the Man From U.N.C.L.E,” introduced by David McCallum: “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.’s popularity and longevity reflects the remarkable contribution of Jerry Goldsmith, Lalo Schifrin, Gerald Fried and others who composed its music,” McCallum rightly declares.

Appropriately, Jon Burlingame, TV-music expert and compiler/producer of FSM’s essential four-volume set of U.N.C.L.E. music soundtracks, is the featured interviewee, providing the authoritative history and appreciation of the music that made the show so trendy and timeless. Burlingame describes Goldsmith’s brilliant main theme as “partly military and partly wild brassy flourish” and explains that “the music of any television show generally reflects the feelings of the show, the time and place that it’s made in and the atmosphere surrounding it. So in the case of U.N.C.L.E., early 1960s, you’re talking about a product of the cold war phenomenon that we were in the middle of at the time. So the fact that the show had this sensibility automatically translated to Goldsmith’s approach musically, in that there is a certain kind of militaristic, but also a kind of laid back, light kind of touch, from time to time, especially in the relationship between Solo and Illya. So you have this kind of two-fold approach in the theme, and I think that’s part reflective of the culture of the time.”

Burlingame notes how both the main title theme and the musical underscore changed direction with each of the show’s four seasons. “Every year the show changed both in tone and there was a new main title sequence, visually… So every year there was a new arrangement of Goldsmith’s theme,” he says. The first season is very straightforward, serious and compelling. For season two, the network asked Lalo Schifrin, then known as a Latin jazz composer who had initially come into the film to score an episode that took place in a Caribbean casino, to modify the Goldsmith theme to fit the lighter, hipper, cooler tonality of Season 2. Schifrin’s title music featured a jazzier rhythmic vibe (shifted from 5/4 to 4/4 time), and added flute and bongo drums. “Goldsmith was furious,” Burlingame adds, “but this is the theme that most people remember.” Season 3’s theme was arranged by Gerald Fried, by then the primary U.N.C.L.E. composer, with a much more upbeat, energetic, jazzy style reflective of the season’s high camp, featuring organ and a bold tenor sax solo. Season 4 returned to the first season’s straight action/adventure approach. Bob Armbruster, the head of music at MGM, arranged the theme, still brass and drums, but with capturing a darker vision of the Goldsmith theme.

Beyond his title music, Goldsmith wrote two other primary themes for the pilot which he developed and varied in the other two episodes he composed. One was a romantic tune that became known as “Meet Mr. Solo.“ “That was a key theme was used throughout the run of the series,” Burlingame explains; it’s often heard during romantic moments, such as at the end of episodes where Solo exits with his latest female conquest. The Main Title theme was occasionally used as a background musical element in Goldsmith’s scores; but his third theme, “The Invaders”, introduced at the opening cityscape in “The Vulcan Affair,” is an action piece “that did not survive beyond Goldsmith’s involvement in first season,” notes Burlingame.

Of the many composers whose efforts enhanced the series, Goldsmith’s were by far the most accomplished scores of series, Burlingame attests. “In those three episodes, Goldsmith takes the theme[s] and twists and turns them and creates variations and develops those three themes that he originally wrote for the pilot and turns them into television scores that are just as good as any of the film scores that he was writing at the time,” says Burlingame, who goes on to describe the notable efforts of later U.N.C.L.E. composers Morton Stevens, Walter Scharf, Lalo Schifrin, Gerald Fried, Robert Drasnin, and Richard Shores. The shift in tone throughout each season is reflected in the music – from the light and often tongue-in-cheek touch of Fried and Drasnin in Season 2, noted for lots of jazz harpsichord in the scores, to the wild comedy and camp (reflecting the influence of rival show Batman) of Season 4, where Fried even used a pair of kazoos as featured instruments in “The Hot Number Affair” and the overt use of cartoonlike music in episodes like “The My Friend The Gorilla Affair.” The 4th season, mostly composed by Richard Shores, returned to an approach that was “much more serious [and] darker, but also jazzy, kind of reverbing back to the approach of the first season, with some electronic keyboards.”

Game Score News

Garry Schyman's score for Bioshock has won two of top-rated the video game awards, earning “Best Original Score” at The Spike TV Video Game Awards on December 9th, and “Best Original Soundtrack” at the X-Play Best of 2007 Awards on December 17.Schyman’s score for BioShock is described by the Sci-Fi Channel as “Remarkable and remarkably good… a feast for the musical connoisseur” and Music4Games.net reviewed the score as featuring “…intimate orchestral, aleatoric passages, virtuoso solo, masterful piano and even environmental sound design. Dark brooding strings that never ever overpowers anything but fleeting thoughts.”

(Read my interview with Schyman on this impressive orchestral gamescore in my November 19th column.)God of War II (Cris Velasco, Gerard K. Marino, et al), Mass Effect (Jack Wall & Sam Hulick), and Halo 3 (Martin O’Donnell & Michael Salvatori) were also nominated for Spike TV awards.

For more details, see:

www.ifilm.com/collection/24055/show/23733

www.g4tv.com/xplay/index.html

Randall Larson was for many years senior editor for Soundtrack Magazine, publisher of CinemaScore: The Film Music Journal, and a film music columnist for Cinefantastique magazine. A specialist on horror film music, he is the author of Musique Fantastique: A Survey of Film Music from the Fantastic Cinema and Music From the House of Hammer. He now reviews soundtracks Music from the Movies, Cemetery Dance magazine, and writes for Film Music Magazine and others.