|

||

|

Soundtrax 2024-11B: Special Edition

December 2024 –Interview SpecialComposer Stuart Hancock on Scoring KENSUKE’S KINGDOM

Award-winning composer Stuart Hancock’s most recent work on the animated epic KENSUKE’S KINGDOM helps establish the children’s book adaptation as one of the year’s most sweeping and heartfelt stories. The film is a good old-fashioned adventure, rendered in gorgeous hand-drawn 2D animation. The source material was written by celebrated British author Sir Michael Morpurgo, who is most well-known for his book War Horse, which was also adapted into an acclaimed film by Steven Spielberg.

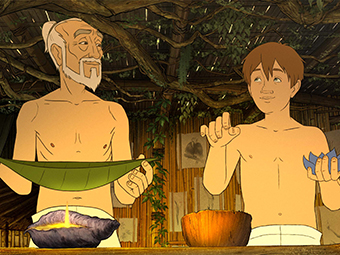

The 3-time BAFTA Award-winning hand-drawn animated feature follows the epic adventure of Michael, a young boy who sets off with his family on the sailing trip of a lifetime. Excitement turns to terror when a violent storm erupts, and Michael and his dog, Stella, are swept overboard. They are washed up onto a remote island, frightened and struggling to survive. Michael soon discovers he is not alone when confronted by Kensuke, a mysterious Japanese man who has secretly lived on the island since World War II and is angry at Michael’s arrival. However, when poachers threaten their fragile island paradise and the animals there, Michael and Kensuke join forces to save their secret world.

The score for KENSUKE’S KINGDOM is big, traditional, and symphonic. Stuart handled every aspect of the music production – composition, orchestration, music editing, mixing supervision, budget handling, etc. Of course, he collaborated closely with directors Neil Boyle and Kirk Hendry, who initially conceived the project almost as a silent movie, as there is very little dialogue between the two lead characters, who do not speak each other’s language. The music, therefore, plays a pivotal role in the storytelling, featuring a 60-piece orchestra and a 35-piece choir. One of the film’s more moving moments comes via a flashback of the elderly Kensuke. As he reflects on the fate of Nagasaki during his time as a soldier, Stuart employs a choral arrangement of the Japanese folk song “Sakura Sakura,” featuring an 8-year-old Japanese girl singer and star Ken Watanabe. The film also stars Academy Award nominee Sally Hawkins and Academy Award winner Cillian Murphy. KENSUKE’S KINGDOM has so far received 21 wins and 2 nominations, with Hancock winning 11 awards for his musical score, including Best Music, 2024, from the British Animation Awards as well as the Music + Sound Awards, International (MASA), 2024, Best Original Composition/Feature Film Score (International).

Watch the film’s trailer, via YouTube:

Q: How did you become involved in KENSUKE’S KINGDOM, and what were the filmmaker’s ideas regarding its musical iterations??

Stuart Hancock: I’d worked with both of the directors before, with Neil Boyle, who is a very experienced animator; one of his first credits was animating on WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT in the ‘80s, and he did SPACE JAM as well, and much else. I wrote music for him for a short film called THE LAST BELLE (2011) and met Kirk around the same time. So I scored that with him, and he recommended me for another animation project in 2016, a TV special called WE’RE GOING ON A BEAR HUNT, and I got that gig thanks to him. Then, fast forward a few years, and KENSUKE’S KINGDOM comes about. I’d worked with both directors and LUPUS FILMS, who produced BEAR HUNT, so I’ve had good connections there. And actually, my first connection on KENSUKE’S KINGDOM was in 2016, when Neil and Kirk were putting together a two-minute test animation to try and sell the idea and raise the finances, and they asked me to write music for that back in 2016

Some of the themes I wrote for that two-minute test became part of the actual score when it came to writing it. In terms of their musical ideas, like me, they grew up watching ‘80s adventure movies with John Williams’ scores – we’re all huge fans of those movies and their scores, so their temp score on the movie was full of John Williams, bits of E.T. and HARRY POTTER, and this, that, and the other! Lovely, rich, old-fashioned storytelling withsymphonic scores, so their heads were very much in that space, which suited me perfectly. It’s the style I like to write in, so I was a very happy camper!

Q: What were your initial thoughts about starting the film when creating the score?

Stuart Hancock: Kirk and Neil treated it almost like a silent film because the bulk of it was set on an island with two lead characters who can’t speak each other’s language – it was a deliberate decision on the part of the screen-writer Frank Cottrell-Boyce, when he was adapting from the original Michael Morpurgo book to strip the dialogue almost to an absolute minimum, because they wanted it to feel like the visuals and the sound design and the music are the storytellers, as much as anything. So the film has lots and lots of space for music to develop, breathe, and inform the story in a way that was such a gift for a composer to work on. The score became quite a symphony, really, in the sense that I had the opportunity to develop themes for the characters and the situations in the movie, and they could develop naturally and coherently in a symphonic way right through to the final scene, where you hear the last incarnations of each of those themes. As you know, the final scene is a poignant goodbye scene, so it draws everything together and lets it go. It’s a very satisfying score to have created in a symphonic way.

Q: How would you describe the score’s thematic ideas as they circulate around Michael and Kensuke’s characters?

Stuart Hancock: We open with a big adventure theme, which I call the Peggy Sue theme because we hear it on the boat in the first scene. That theme is linked not just to the adventure but also to his family, so every time, later in the film, when he’s thinking of his lost family, we hear a rendition of that theme, whether it’s solo piano or some very minimal instrumentation. Kensuke has his chant theme, which he delivers to some of the orangutans in the glade sequence, which was one of the first themes I wrote because they had to be animated. Obviously, you see his lips singing the notes of that. That theme works very well; it has a slightly exotic feel, giving us a somewhat mysterious, otherworldly, non-Western feel. It became more of a sound for the island itself because we hear it subliminally in the score when Michael is first washed up on the beach. You listen to it in the choir and on the strings very subtly in track 8 (“Tide Coming In”). You’re feeling that Kensuke motif in the score before we’ve even met him. By the time we hear him vocalizing it, we’re familiar with it; we’re in that island/mysterious feel, which is threatening until we get to know the character and know that he’s not all bad. He’s just been there a long time, and Michael is an intruder, to start with. As their relationship develops, the music softens, and the slightly dissonant notes I used in the theme tend to thin themselves out slightly.

On the subject of that Kensuke theme, working with Ken Watanabe to record it was a treat. We did a recording session remotely with him in Toyko, which was like 5 a.m. for us! But he was tremendous, such a gentleman and a top guy. He loved working on it and loved the score, which was lovely to hear from him. Ultimately, he gave us a ton of good material to play with for those singing scenes.

Q: Which choir and orchestra did you bring into the project, and how were they used throughout the score?

Stuart Hancock: The choir was a London-based choir called The Holst Singers. I’ve worked with them before; they’ve commissioned a concert piece from me. They’re an amateur but a very high-level amateur choir, so their singers all have day jobs and do their singing in their spare time. They were brilliant to work with; we did a three-hour rehearsal on the material before the day, and then a three-hour session recording with them. The bulk of what I’d written for them is very textural, with a couple of exceptions, the most obvious one being the Nagasaki sequence. At that point, we needed something different out of the score because, obviously, we were flipping to a different animation style to depict that flashback to Japan. And up until that point, I’d only used them in a textural way. But my suggestion was that we do a showpiece for the choir to accompany that scene, and because of the setting and the story element that we’re depicting at that point, it made sense to arrange a Japanese folk song. It was as simple as googling “Japanese Folk Song.” The first one that popped up was “Sakura Sakura in” [The in scale (also known as the Sakura pentatonic scale due to its use in the well-known folk song Sakura Sakura], [see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_scale ] is one of two pentatonic scales commonly used in Japanese folk music]. It has been used in other projects, but it’s such a beautiful, simple, melancholy theme that it became quite an epic arrangement, especially if you get a solo Japanese eight-year-old girl singing it; that first bit of it is pretty powerful.

The orchestra was the Bratislava Symphony Orchestra, so we had two big recording days with them to record the entire score, which was really, really hard work, getting that done in two days – and kind of not something I’d want to repeat – because it should have been three days! But they were tremendous; they worked hard for two days, and we got it all in the can. They’re an orchestra I’ve worked with several times, and I have a good relationship with them. I know they’re good. There’s also a financial consideration in using an Eastern or Central European orchestra, as I’m sure you’re aware, and this was essentially a low-budget film. The music budget was extremely low for what I produced, but I feel I’ve succeeded in making it sound far more expensive than it was!

Q: Another interesting moment is when Kensuke introduces Michael to the family of orangutans living on the island; how would you describe these musical elements?

Stuart Hancock: The scene begins when Michael first encounters them, and he disturbs them. He is secretly drawn to them by hearing their vocal chants echoing around the island. So, musically, that’s the motif I used in those scenes, in various guises. When he’s more at peace with the scenes and the orangutans, that theme is gentler, less dissonant, and more tuneful. By the time we’ve gotten to that point, the other theme to mention at this stage is that, essentially, the latter half of the story becomes a love story. Kirk and Neil made that very clear from the start – we needed a love theme, obviously a sort of father/son companionship, in that they’re bonded over this sense of a loss that they’ve both had, losing their families. Straight after the Nagasaki scene, we hear a solo piano, a new theme at that point, which becomes the new family theme between Kensuke and Michael, and expand that to the family of orangutans. That’s their new family. It’s some fun musical games when you play with these scenes and satisfying when it all gels.

Q: In contrast, you’ve created a pleasing element of danger when poachers come to the island to steal the island’s wildlife, with an eye on the orangutans… an element in profound contrast to the peaceful kingdom of Michael, Kensuke, and the orangutans…

Stuart Hancock: That, again, obviously, we needed something sonically different. When we first encountered contra-bassoons, bass clarinets, and your low brass in the movie, the thrust of it is very, very rhythmic, given the dreadful approach of these horrible men. It’s building up these kinds of churning arpeggios to replicate the approach of the danger, gradually introducing percussion in a way that I hadn’t in the score up to that point. In these more climactic scenes, my percussionist played a bit of taiko and some toms and racked up various percussion layers. The other element I introduced in the orchestration, which occurs in that scene, is a throbbing synth bass. It’s pretty subtle in the mix, but it gives a slight, pulsating texture – because it’s an invasive thing that’s going on after the peacefulness of the choir and the orchestra. It was fun to introduce this nasty undercurrent into that music.

Then, the scene’s climax is the death of one of the primates, which involves the choir singing – it’s not intelligible in the words, but they’re singing Indonesian words. I don’t want to give any spoilers! It was a big scene to deal with, and I remember spending a couple of weeks writing the first draft of it. I got it right, with a few revisions and refinements after that. The pulsing rhythm was the thrust of that scene.

Q: You previously scored the historic documentary HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI: 75 YEARS LATER (2020); I’m curious about what kind of touchstone you might have had between those two films, as well as the difference between scoring for commercial vs. narrative work.

Stuart Hancock: Yeah, it’s a strange coincidence that I did them both. I officially came on board KENSUKE'S KINGDOM in November of 2020, and I worked on the NAGASAKI documentary in early 2020, so I’d finished one before I started on KENSUKE’s KINGDOM. I remember playing my score to Neil, the director at the time, showed him bits of it. At that point, I hadn’t gotten the job, and he said, “Well, NAGASAKI comes into KENSUKE’S KINGDOM, he latched onto the pathos that I’d achieved on the documentary. Musically, they don’t relate to each other at all, but the way I immersed myself in that story through the documentary was purely a coincidence that it cropped up again in the animated movie. The documentary came out on August 2, 2020, on the History Channel, on the 75th anniversary of the bomb drops on August 6th and 9th, 1945.

Q: What’s coming up next that you could talk about?

Stuart Hancock: I’ve done an excellent short film recently, called LARGO, for a pair of young directors (Max Burgoyne-Moore, Salvatore Scarpa) about a Syrian refugee who’s made his way from war-torn Syria to try and make a new life in the UK. Strangely, it resonates with KENSUKE’S KINGDOM because he arrives on a boat and gets into trouble at sea. It’s, again, quite a poignant film. But I’m pretty excited about that one because it’s really good.

I think it’s going to have its festival run next year. The production company is Slick Films; they were behind a film called THE SILENT CHILD, which won the Best Short Film Oscar. And I could hint at a couple of projects in the pipeline, but I can’t offer much detail yet. One of them is a wartime comedy/drama; the other is a kind of spy-caper comedy; both of these projects are raising their finances and hopefully will go into production sometime next year.

But in the meantime, my bread-and-butter work is in commercials and advertising work. That’s what pays the bills! I’ve got a couple of American ads, one for Green Mountain Energy which is a nice little animated one. I’ve also done music for two Amazon Business adverts on TV in the States. So, that’s sort of the baseline of my work that pays the bills, and now and again allows me to spread my wings and do something wonderful like KENSUKE'S KINGDOM!Listen to the Nagasaki/Sakura Sakura sequence from KENSUKE’S KINGDOM: